The Oscar Winning Editing of Dunkirk

- The making of Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk

- Lee Smith on the Oscar Winning Editing of Dunkirk

- Hans Zimmer’s Epic Score for Dunkirk

Christopher Nolan’s IMAX sized, suspense film, Dunkirk, was one of my favourites from 2017. Shortly after its release I started putting together this post, and fresh off the back of it’s Oscar success I thought it was time I published it.

Dunkirk won 3 Oscars for Best Film Editing, Best Sound Editing and Best Sound Mixing, although it was also nominated for Best Director and Best Picture, Best Cinematography and Best Production Design.

More often than not the winner for Best Editing and Best Picture tend to be the same film, but whilst The Shape of Water, won Best Picture this year, the structurally intricate and narratively interwoven Dunkirk clinched the statue.

It’s an interesting film to dissect for a number of reasons, not least because it’s a Christopher Nolan film, but because of the specific techniques that went into it’s construction.

In this post we will look at things like the Shepard Tone, Nolan’s concept of ‘snow-balling’, shooting and editing for IMAX and a whole bunch more.

This 3o minute behind the scenes extra was released by Warner Bros. in the run up to the Oscars.

I suppose as a way to increase the odds of winning, but helpfully for us it delivers a window into the film’s challenging and logistically complex production, and Nolan’s collaborative process with his key team members.

Buy Dunkirk on Amazon Global Stores

Dunkirk is available on a 2 disc Blu-ray, costing [amazon_link asins=’B074ZVMJYS’ template=’PriceLink’ store=’jonelwfiledi-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’c11921e9-2214-11e8-9a20-4b1a9ab903da’] in the US, with the following special features, with the ‘Turning Up the Tension’ instalment focuses on the editing process specifically.

- Creation

- Revisiting the Miracle

- Dunkerque

- Expanding the Frame

- The In-Camera Approach

- Land

- Rebuilding the Mole

- The Army On the Beach

- Uniform Approach

- Air

- Taking to the Air

- Inside the Cockpit

- Sea

- Assembling the Naval Fleet

- Launching the Moonstone

- Taking to the Sea

- Sinking the Ships

- The Little Ships

- Conclusion

- Turning Up the Tension

- The Dunkirk Spirit

Buy the Dunkirk 2 disc Blu-ray on Amazon Global Stores

Christopher Nolan on Dunkirk

This interview with director Christopher Nolan from Film 4 helps set the scene for his approach, ambition and techniques in bringing the multi-stranded Dunkirk from idea to IMAX screen.

Everything for me is about intensity and suspense… I approached the structure from a very mathematical and geometric point of view.

…You have years of planning as a filmmaker for an audience who sits there for under two hours, and receives. And so what you’re trying to do is mess with and alter the very rhythms of filmmaking…

I have a particular fascination with third act structures, that I’ve been putting together and how they have what I consider a snowballing effect. Whereby, you’re cross cutting parallel action and as it comes together 2+2 starts to equal 5, 6, 7, 8. And you get this kind of snow-balling of momentum. And I wanted to apply that very rigidly to the entire film.

In an interesting article in the UK’s The Telegraph, written by Nolan himself, you can hear a bit more about the making of the film, from Nolan’s own perspective:

We were very, very clear [when pitching to Warner Bros.] that rather than using CG recreations, we were going to try to find real ships and planes that matched those from the time as closely as possible.

We would find the actual planes, and fly them in dogfights against each other, and get the camera and the actor up in the plane. We were going to do this for real to the extent that we could.

Nolan talks about numerous aspects of making the film, including chatting to Steven Spielberg and Ron Howard about the best way to shoot on water:

I spoke to filmmakers who’d shot on open water – Steven Spielberg, Ron Howard – and got some great advice.

Both Steven and Ron felt that the best camera mode for shooting on a boat is handheld – even though we were shooting IMAX format – because the camera-men could steady themselves against the movement of the boat.

That proved to be the case. That’s the way you get it done.

You can read the full article here.

If you want to listen to 30 minutes of Christopher Nolan and Edgar Wright chatting about making movies, then this podcast from the Director Guild of America is what you’re after.

Christopher Nolan narrates an anatomy of a scene from Dunkirk, describing both his research and production processes to craft a dramatic scene.

Understanding the IMAX format

If you had the chance to see Dunkirk in IMAX, with a 70mm film print on a really big screen (IMAX screens tend to differ quite a bit!) then you saw it in the way the director intended.

Personally, I’ve seen Dunkirk and Interstellar at the Science Museum IMAX and it’s always a special experience, if you’re in town I’d highly recommend going there specifically.

In these making of videos are articles you can get a bit more info on the in’s and out’s of the IMAX format and Dunkirk’s use of it, with about 70% of the film shot on 65mm film.

In this short video you get an inside look at what goes into printing, distributing and projecting Dunkirk in 70mm.

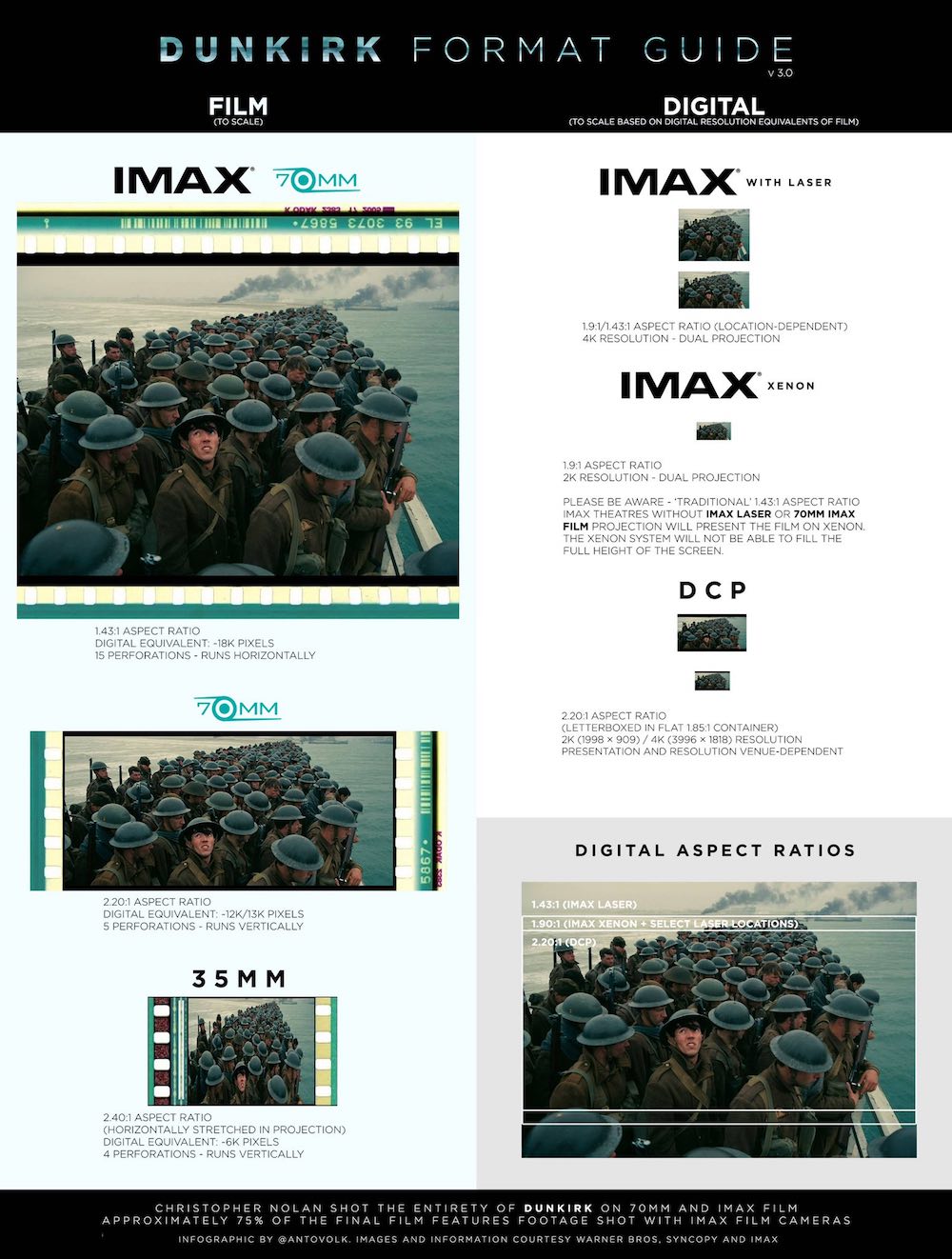

Not all IMAX cinemas are created equal and there’s quite a bit of difference between the size of a screen showing a 70mm film print and a 2K digital IMAX presentation. The film was also released in a number of different formats.

This guide was put together by Anton Volkov, who tweeted it here. This Reddit post helps to spell out the qualitative differences in screening experience.

Basically, back in the day, IMAX meant one thing, and one thing only.

A massive screen with a very specific 1.43:1 aspect ratio that’s more of a square than the wide rectangle most movies are shown in, and a specific type of film called IMAX 70mm.

Despite the name, it’s a completely different format to 70mm. Basically, while 70mm is much higher quality than other film types, IMAX 70mm is far, far better than even normal 70 mm.

(I think the 70mm this writer is referring to is essentially the same as the 65mm below, just with the 5mm of soundtrack included.)

This blog post on High Def Digest details on man’s 518 mile trip to see the film as Nolan intended, with a good explanation of what goes into the sound and picture of an IMAX showing.

As Dunkirk switches back and forth between IMAX 70mm film and 65mm film, this was a distraction for some, especially in the 2K screenings, but I totally failed to notice it when I saw the film.

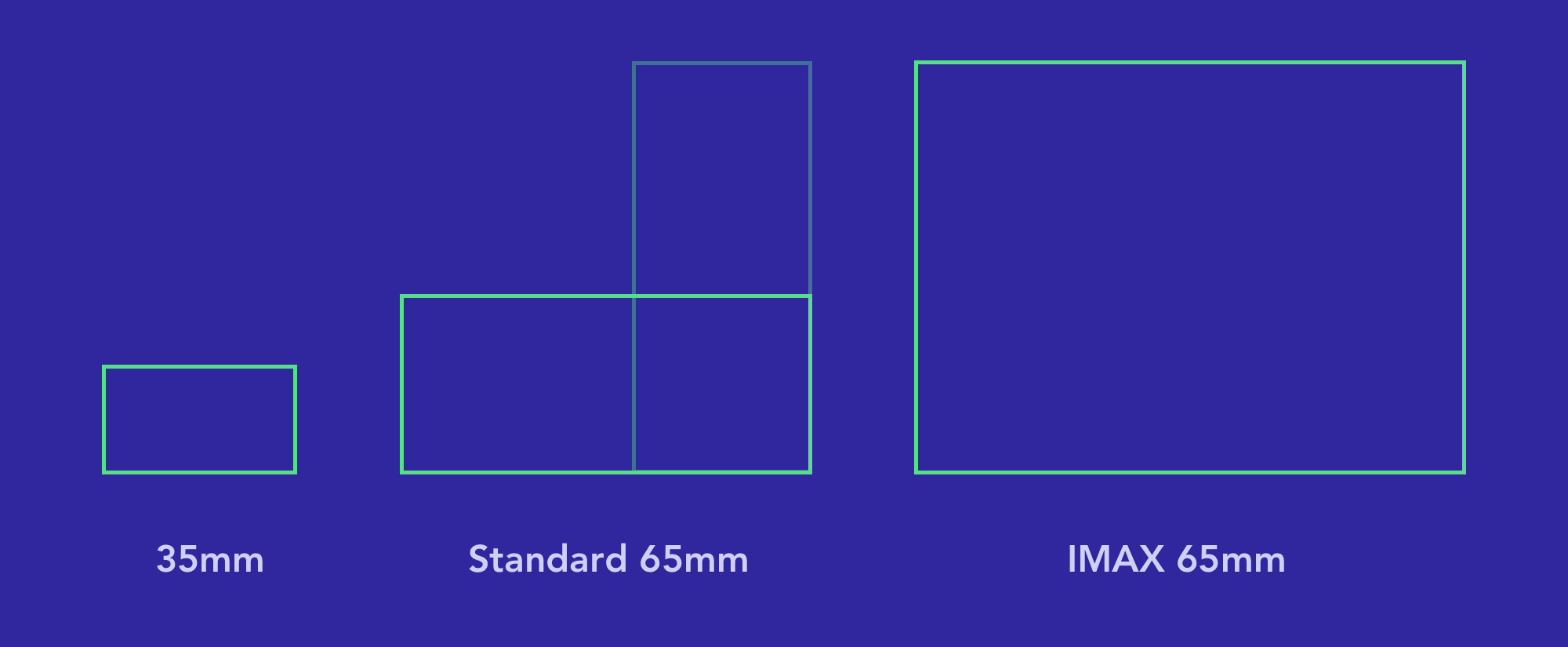

It sounds like it shouldn’t be that different, but as this excellent post from David Kong of Frame.io’s blog details, it’s a confusingly similar sounding name for something very different:

In spite of the similar-sounding names, IMAX 65mm and standard 65mm have different sizes and different aspect ratios.

The names are misleading because IMAX 65mm is 65mm tall, while standard 65mm is 65mm wide, resulting in two completely different types of film being known by the same number.

Also, you may have heard that the film was projected at IMAX 70mm, not IMAX 65mm. This is another issue of confusing terminology.

The image is exactly the same size in both cases—the extra 5mm is used by the soundtrack during projection. So you always capture IMAX at 65mm and display it at 70mm, but the image is not scaled or cropped in the process.

Same thing with standard 65mm film—it’s projected at standard 70mm (not IMAX 70mm). – David Kong

We’ll come back to David’s superb post in a bit!

Lee Smith on Editing Dunkirk

Oscar winning editor Lee Smith has edited all of Christopher Nolan’s films since Batman Begins (2005), and also edited Spectre and Elysium.

When I read the script I thought this could be a 100 million dollar art movie, and it could be the end of all of us. But thankfully, it wasn’t. – Lee Smith

In this short interview from BAFTA you can get to hear Lee’s perspective on what it’s like to build a working relationship with a director from first interview to long-term multi-picture scenarios. He then gets into the detail of editing Dunkirk.

One of the interesting tidbits on the post production process Lee discloses, is their habit of screening the film in Lee’s edit suite every friday, to test how the endless shuffling of the scenes and crossing points, was effecting the narrative flow.

We spent a lot of time perfecting where we moved from land to sea to air and back again.

Probably in the first construction it was quite confusing because a lot of times you went back and you’d been away from one of the components for too long a period, so you’d be thinking “I’m not sure where I am or what’s happening.”

And then it was just a matter of continuous processing, to get it to the point where we thought the audience could sit through this reasonably complicated path way, still enjoy it, and even if a few of them didn’t quite catch what was happening, they would catch up with it. Good confusion versus bad confusion.

And that was something we tested and tested and tested… we did a lot of screenings of Dunkirk until we thought we had it exactly where we needed it. – Lee Smith

Another interesting fact is that they finished and projected a 70mm cut of the film, including visual effects for the studio at the end of the contractual 10 weeks that director Christopher Nolan gets to make ‘his version’ of the film. Which sounds like a pretty epic achievement!

Steve Hullfish’s Art of The Cut interview with Lee is also well worth a read. In their conversation they cover topics like working on IMAX, building suspense, Hans Zimmer’s score and the film’s intense sound design and a whole lot more.

In this extended quote you can pick up a ton of wisdom about editing efficiently for finishing a whole film, not just a single scene.

HULLFISH: We talked during our last interview about the fact that you don’t obsess about your initial assembly. Your assistant editor says you cut very quickly — which is something you’ve also said. I’ve talked to other editors that say, “I have to work and work on a scene until it’s perfect before I can put it in the first assembly.”

SMITH: It’s not that I don’t obsess. I just do it how I want to do it, and I guess the word obsession would mean I would be not convinced that I was doing it right. And I’d have to keep doing it and doing it or doing it.

Whereas for me, from an energy standpoint, I get it right as quickly as possible and I’m not saying that I don’t have scenes that are more tricky than others. But I’m not sitting there second-guessing my own first guess.

So if obsession is that you just keep working on something until you’re happy, but to me, that feels like you’re fussing with it to the point where you might start to lose what is that initially excited you about it.

The process of the assembly is that you are going to go through the film again and again and again and again and again and again.

For me, it just keeps me fresh to keep looking at it. It makes me so I’m not averse to changing things and looking at different ways of doing it because I didn’t arrive at that first cut with blood and sweat.

And a lot of how I originally cut it is what is in the movie. And sometimes those are the most complicated scenes in the movie.

And the ones that seemingly are simple are the ones that you end up putting 50 versions together because for some reason that scene is not doing what it needed to do. And probably the reason you keep going back to it is there’s an inherent problem with that scene. So you’re really having to hammer it to make it do what you want it to do.

HULLFISH: I think when we originally talked about this it was a discussion of: “What’s the point of working it and working it and working it as a solo scene, when you need to see it in the context of the overall movie and story and even just to feel it in the position of the scene immediately before and after it.”

SMITH: Yes that’s true too.

The other reason is: that I can’t hope to know — out of order, and in my first pass — if I pick the exact right things because I’m picking the things that appeal to me right now, out of context.

I mean, of course, I’ve read the script and I know what I’m doing, but having said that, the film, once it’s joined together… the quicker you can get the film together in a good sensible fashion and start watching it as a movie the quicker you start understanding where the weaknesses are.

I’ll frequently let assistants cut things and invariably they’re sweating bullets about how to start the scene and I’ll ask them if they have seen the scene before the scene they’re cutting, and they’ll say, “It’s not shot yet.”

And I’ll say, “Well, then you don’t know how to start this scene, so pick whatever you want and give as little thought as humanly possible because you might be right. But the odds are you might be wrong and you’re obsessing about something that you don’t know the answer to that yet.”

You can only answer that when you’ve got everything together. And you look at the transitions and you look at: “Should I be in closeup when I start? Should I be in a wide?” and you can spend three days cutting a sequence that really you should have spent three hours cutting because you don’t know what’s the shot you’re coming from… you don’t have it.

And that’s the assembly process.

Now what will happen is when I get that next scene I’ll join those scenes immediately together and then I’ll modify the cut. I will always be recutting my initial assembly the whole way through the assembly process. I never leave anything alone.

Read the whole conversation between Steve and Lee here.

This Guy Edits takes a look at the editing of Dunkirk in this excellent video essay on how it crafts a feeling of rising suspense for nearly two hours and breaks down the intricacies of its ‘multi-braided’ narrative.

We wanted the language of suspense, which is the most visual of cinematic languages. You can create empathy for characters just by virtue of their physical situation.

One of the most interesting bits to me in this essay was the breakdown of the film’s three strands, which you can see more of if you sign up to the This Guy Edit’s Patreon community. (I recently interviewed Sven about this here.)

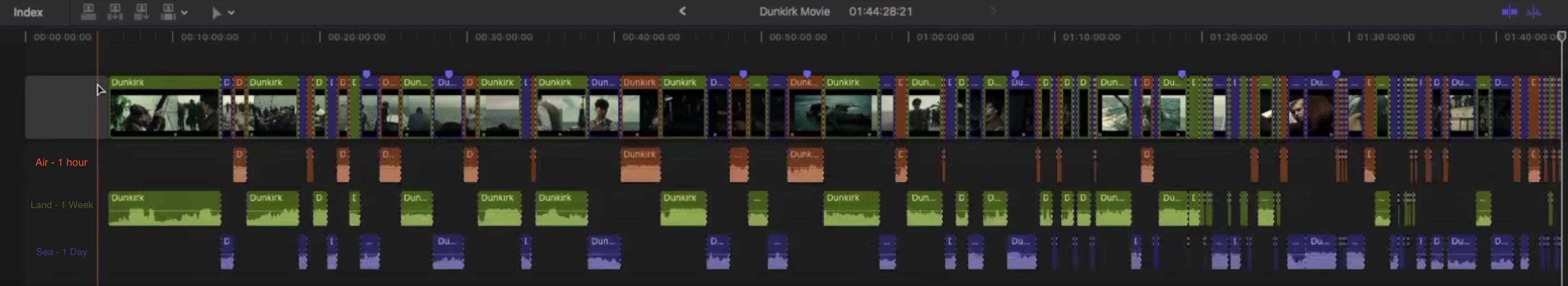

This is a handy way to use FCPX’s roles feature to visually understand your projects narrative structure. In this screenshot from the video essay red is for the air strand of the film (1 hour of ‘real time’), green for the land (1 week) and purple for the sea (1 day).

You can readily see how the scenes get shorter and intercutting gets progressively more intense towards the climax of the film.

Associate Editor John Lee on Dunkirk’s Post Workflow

In another very detailed post Steve Hullfish interviews Assistant Editor John Lee (who has an Associate Editor credit on this film) on the complex film and digital post workflow required to get Dunkirk to the finish line, in all of it’s various formats.

It’s a really fascinating read, that you might want to take your time absorbing. Here is John on screening dailies on location:

We’d send the exposed negative back to LA. For the [65mm] 5 perf material, it would be processed and printed and screened by our crew in LA. Then they’d telecine the 70mm print.

Our Avid assistants would sync in the Avid and spit out a WAV file onto a disc and they’d send us the print and the sound.

We had sourced a 70mm projector in Paris and we got our favourite projectionist from London and we built a great little theatre in Dunkirk for dailies. We’d play the sync sound on a Fostex DV40. So on location we had 70mm dailies screenings instead of a reduction print. It was terrific and we took that 70mm projector from place to place with us.

The IMAX went through a different path. If you print up all your IMAX, it’s going to cost way too much plus you’d need an IMAX theater to screen it. So we made 35mm reduction prints instead.

To get that 35mm reduction to us in a hurry, we didn’t sync it actually. The team would check it in LA at FotoKem and then they’d send it to us and we would screen it without sound because basically the IMAX was all of the stuff that was action so the sound didn’t matter to Chris and he said he’d rather get it there a day earlier and see it without sound.

We had a screening trailer that we parked right next to the theatre we built and we would screen 35mm reduction print of all the IMAX material in that trailer on an Arri LocPro.

Then we would send the 35mm reduction print back to our crew at Warner Brothers and they would telecine it and sync it up.

Then they would send Avid media to us on location and I would download it at my end and I’d give it to Lee and he would start cutting.

Lee Smith screens his current cut in a movie theater once a week to be reminded of the size and scope of the project. It also gives him the audience experience. #iava2018

— Jamie Cobb (@jamiecobbeditor) March 3, 2018

Lee Smith’s biggest challenge cutting Dunkirk was telling a clear story visually. Couldn’t rely on dialogue to tell the story. #iava2018

— Jamie Cobb (@jamiecobbeditor) March 3, 2018

Editor Jamie Cobb tweeted these nuggets from the 2018 Invisible Art, Visible Artists panel discussion with all of the Oscar nominated editors for 2018. Hopefully a full recording of the event will appear online soon!

There are a 17 clips from the event online here.

Colour Grading Dunkirk

Returning briefly to David Kong’s superb article on the workflows of all of the 2018 Oscar nominees for Best Editing, it’s well worth jumping over to Frame.io to read the whole thing as it provides a really interesting comparison of the post production schedules, hardware, dailies processes, colour grading and distribution of the 11 nominated films.

Of these 11 films, Dunkirk was the only film to do an optical print with no digital intermediate. This was again a personal aesthetic choice by Christopher Nolan to avoid the digital color tools and restrict the color treatment to the limited tools of the traditional photochemical color-timing process.

In this interview from The Credits you can read about how Fotokem colorist Walter Volpatto spent three months trying to faithfully reproduce that photochemical process for the digital release of the film.

Our goal was to make sure the digital version of this film conveys the same feeling as a photochemical print.

We started by profiling how the negative and positive react to light. Can the digital and film match perfectly? No, but we used all the technical and creative expertise in our facility to make it as precise a process as possible.

It took us three months to keep all the nuances of Dunkirk intact, a movie with a lot of blues, and a lot of drab military colors. It’s very easy to saturate those or put contrast back, but we didn’t want that.

In addition to the color science pipeline, we played the film and digital scenes side by side in our DI theater so we could be sure the two prints were as similar as possible. It was a privilege to see a photochemical print of Dunkirk.

I was holding the hero print of Dunkirk in my hand, threading it on a 70 mm projector, thinking ‘I better not scratch this!’

In the 10 minute video interview with Walter (above) from Post Perspective, you can hear how he tackled the very different challenge of grading Star Wars: The Last Jedi, plus his thoughts on the future of grading and why he’d rather be watching uncompressed HD, than 8K, in his home.

Hans Zimmer’s incredible score for Dunkirk

One of the things that was immediately apparent when you watched Dunkirk in the cinema was how loud and unrelenting the sound design was. The 70mm IMAX screening I attended at the Science Museum even warned you about it before you went in.

This popular video from Vox breakdowns what the Shepard Tone is and why it is so integral, not only to the sound design and score of the film, but also it’s narrative structure as a whole.

Here is a quote from a Business Insider article, in which Nolan explains it himself:

There’s an audio illusion, if you will, in music called a ‘Shepard tone’ and with my composer David Julyan on The Prestige we explored that, and based a lot of the score around that.

It’s an illusion where there’s a continuing ascension of tone. It’s a corkscrew effect. It’s always going up and up and up, but it never goes outside of its range …

And I wrote the script according to that principle. I interwove the three timelines in such a way that there’s a continual feeling of intensity. Increasing intensity.

I wanted to build the music on similar mathematical principals.

So there’s a fusion of music and sound effects and picture that we’ve never been able to achieve before.

In this Post Perspective interview another consistent collaborator, Supervising Sound Editor Richard King, shares some insights into shaping that intense audio atmosphere.

King was looking for the sound of an “air ballet” with the aircraft moving quickly across the sky.

“There are moments when the plane sounds are minimised to place the audience more in the pilot’s head, and there are sequences where the plane engines are more prominent,” he says. “We also wanted to recreate the vibrations of this vintage aircraft, which became an important sound design element and was inspired by the shuddering images.

I remember that Chris went up in a trainer aircraft to experience the sensation for himself. He reported that it was extremely loud with lots of vibration.

Listening to Hans Zimmer’s intense score whilst you’re working is a particularly visceral experience on a decent set of headphones!

If you want to learn more about filmmaking from Hans Zimmer, check out my detailed review of his masterclass here, including 5 lessons film editors can take away from the course.

Dunkirk Sound Design Secrets

I just found these excellent clips from The Sound Works Collection, which includes a discussion from the Oscar winning sound editors and designers of their work on the film.

Dunkirk Visual Effects

In another BAFTA video you can learn about the Special and Visual effects on Dunkirk, from four of the key department heads, who were tasked with figuring out how to bring Nolan’s vision to reality.

Historical Inaccuracies in Dunkirk

This Looper video breaks down ‘7 lies’ (they’re not really lies) just historical inconsistencies where the filmmakers needed to take artistic license in order to make the film the story they chose to tell. It’s not a 2 hour documentary, after all.

That said, I think it’s important to highlight where things like the real mix of nationalities and ethnicities involved in the historic evacuation of Dunkirk are have seemingly been glossed over or marginalised. There’s a lot of white faces in the film when in reality the troops on the beach were very mixed and the crucial role played by the French isn’t really depicted.

It erases the Royal Indian Army Services Corp companies, which were not only on the beach, but tasked with transporting supplies over terrain that was inaccessible for the British Expeditionary Force’s motorised transport companies.

It also ignores the fact that by 1938, lascars – mostly from South Asia and East Africa – counted for one of four crewmen on British merchant vessels, and thus participated in large numbers in the evacuation.

This article from the Guardian has some real axes to grind, but it fills in some important historical details.