The Making of The Revenant

The Revenant looks like one brutal journey. Not only for the central character but also for the cast and crew. Shot over the course of almost a year in deepest Canada, the United States and (seeking more snow) the very tip of Argentina. But hopefully all that hard graft will be worth it. In this making of post I’ve brought together the best videos, articles and interviews I could find on the making of this epic film.

UPDATE – 45 minute Making of Documentary

It’s pretty rare that you get to see extended making of documentaries, so it’s nice that this 45 minute making of The Revenant documentary has been produced, although it largely focuses on some of the films themes and their modern day implications, rather than the day-to-day challenges of producing the film.

But the documentary has been shot in a pretty stunning fashion itself and poetically charts the filmmaking process, with plenty of exclusive behind the scenes footage, rather than EPK fodder. As a quick aside, two of the best feature length making of films I’ve seen are for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia and Full Tilt Boogie, for Dusk Til Dawn, which are the closest thing a ‘making of’ can probably give you to that ‘living on set feel’. That or the LOTR dvd extras.

Filming The Revenant

As an introduction to what The Revenant is all about, this Anatomy of a Scene from the NY Times website, will give you a sense of what Director Alejandro G. Inarritu was out to capture and the kind of acting it takes to crawl backwards into a freezing river wearing a bear skin rug.

“If we ended up in greenscreen with coffee and everybody having a good time, everybody will be happy, but most likely the film would be a piece of shit.” Revenant is about survival, he says, and the actors and crew benefited from having to make it in nature.

It was apparently a more hellish shoot than you might imagine it could be, and the decision to shoot only with natural light made it all the more challenging. You can read a lot more about these challenges in this very detailed Wikipedia article here. You can hear more from Leonardo Di Caprio in this extended Wired interview, featuring the quote below.

[W] What was the worst part?

The hardest thing for me was getting in and out of frozen rivers. [Laughs.] Because I had elk skin on and a bear fur that weighed about 100 pounds when it got wet. And every day it was a challenge not to get hypothermia.

[W] How prepared was the crew for that? Did they say, “Well, we’re going to throw DiCaprio into a frozen river, we better have some EMTs here”?

Oh, they had EMTs there. And they had this machine that they put together—it was kind of like a giant hair dryer with octopus tentacles—so I could heat my feet and fingers after every take, because they got locked up with the cold. So they were basically blasting me with an octopus hair dryer after every single take for nine months.

When we were shooting it was terrifying to know that it was a clock-watching precision kind of thing. But to be doing one or two takes a day because it was at the end of the day. The adrenaline was so real, that every day was terrifying knowing that we have rehearsed so much and that was the only hour to get all that we have done.

This half hour conversation between Michael Mann and Alejandro at a Director’s Guild of America screening is filled with fascinating insights not only on the production process but also the visual aesthetic and filmmaking language, he and Director of Photography Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki were trying to capture.

There is also a nice write up on from Indie Wire on the experience of making the film from numerous cast and crew, which is also worth a look.

As someone who doesn’t like appearing on camera it seems that the Studio can make that happen, and in this marketing featurette Chivo talks (very) briefly about his work on the film. I believe they shot on 24 and 40 mm lenses most of the time.

We realised that very wide lenses allow us to really engage the audience in the movie in a very visceral way. We were able to have close up’s of Leo and still have all the environment present.

For a much longer and more detailed interview check out this article on Indie Wire, which features a few more technical details about Lubezki’s experience of shooting on the as then untested, Alexa 65:

Somehow this camera truly translated what I was living and feeling in that place into images. Usually you look up into the landscape and it’s never there— you’re shooting fragments. But this one, because of the size of the chip [54.12mm x 25.58 mm] and the quality of the image [6560 x 3102 resolution] and how clean it is, it does feel like a window into that place. That was the other reason to shoot digital instead of film.

I didn’t want to have grain, I didn’t want it to feel like a representation of the experience of Glass. I wanted to feel as if you are walking with him. I wanted it to be visceral, I wanted you to feel his breath and see his sweat, the tears coming out of his eyes. Usually we don’t do this outside—we use longer lenses trying to make everything beautiful.”

UPDATE – The Revenant Cinematography Breakdown

DP Matt Workman, who runs the excellent looking Cinematography Database, recently put together this detailed breakdown of some of the technical and creative work going on in the film. It’s really interesting to hear what he can bring out of a few bits of B-Roll and some screengrabs. An excellent watch and well worth the time.

A really short, but beautiful ‘video essay’ on stillness in The Revenant, by Tom Williams.

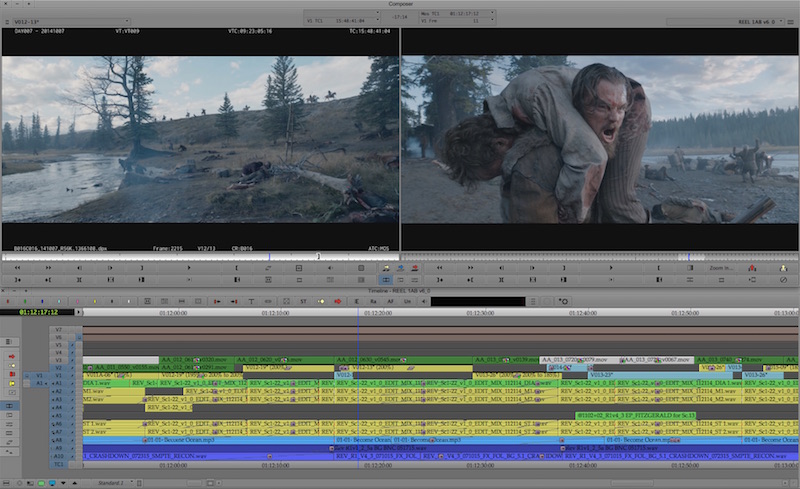

Editing The Revenant

Editor Stephen Mirrione is actually one of my favourite editors and in this, characteristically excellent, interview from Steve Hullfish over on Pro Video Coalition, you can hear from him at length.

This is his fifth film editing for Alejandro (21 Grams, Babel, Bitiful, Birdman and The Revenant) and represents his third Oscar nomination too. He previously won in 2000 for Traffic and was nominated for Babel in 2006. Here are a few select quotes from Steve’s must-read interview, which covers a lot of interesting ground from the unique VFX pipeline, Stephen’s preferred method of tackling dailies and a lot more.

On collaborating with a director:

To me, the beauty and attraction of feature film is that it’s one of the few collaborative art forms where the director really is the one true voice of the whole movie. That’s what I love. And the only way to really accomplish that is to listen and understand and respond to the journey that the director wants to go on. I think that’s the way most editors approach their work. It’s served me very well to do that.

On cutting rehearsals faster than dailies:

One of the things we learned from ‘Birdman’ was the value of cutting all the rehearsals together. We also put a system in place where we were making these low res files off of the video-tap… All those files would get sent to me either on set or back in Calgary where I was working most of the time. And I could then take that material, review it and cut it together so that by the time they got around to lunch and they were shooting the actual scenes that those dress rehearsals were for, Alejandro could then get the information he needed to make any subtle changes he needed to do.

On being a storyteller:

A lot of good storytelling has to do with point of view, making sure your audience understands what the characters are thinking and feeling and how different characters can perceive the same moment in different ways. As with a lot of things, there is an instinct that leads you in making those decisions, if you make all your creative choices too analytically you end up with something a bit cold in my opinion. So by doing it again and again, you become better at trusting your instincts. In that way, it is a skill that you can become better at through lots and lots of practice.

As the awards season marketing picks up pace, there are more and more interviews with the Oscar contenders available online, which is good news for us! Here are a selection of some of Stephen’s best interviews.

Studio Daily has a nice long interview with Stephen that covers his experience of production in quite a lot of depth, as well as his interaction with VFX and perspective on performances.

When I’m on set in a trailer on a laptop, I can work on scenes in a particular way, but it’s a very different kind of space. I’m not going to be able to sit down and take my time to find the rhythm of a scene, especially when I’m putting together a scene for the first time. In order to look at all the dailies in the right environment, I need to go back to the edit suite, where I know I won’t have any distractions for four or five hours. On set, it becomes more about going through things in a more technical way.

Awards Daily has a fairly informal interview which also has some nice insights in it too.

AD: What was the longest sequence to edit, in terms of time?

SM: You know, it’s funny because the sequences that you would think were the longest actually weren’t because I had to work super-fast to lock them to turn over for visual effects. I would say the sequence in the movie, that kind of middle section when Leo is finally by himself and Fitzgerald and Bridger are by themselves, the structure of that section took us, I would say, the longest to figure out and figure out what the right order was.

In the script, it went back and forth a lot more, I would say, it was a more traditional mode of storytelling. But, in watching it, it started to feel very episodic and you started to lose a little bit of the connection and through-line. By rearranging and moving a few scenes forward so that they informed other scenes, something happened and the magic just kind of clicked into place. That took the longest to figure out because it wasn’t clear and there was almost an infinite number of possible combinations to find it.

UPDATE – AOTG Interview

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/245303080″ params=”color=ff5500″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]The Art of The Guillotine has a fantastic 20 minute audio interview with editor Stephen Mirrione on his process of cutting the film, with some really great insights. There’s a full transcript of the interview here, over on the AOTG.com site.

The thing with this that was tricky editorially was, it took actually quite a while for Alejandro to even find the rhythm of the movie, whereas, especially after coming off of Birdman, where we had to find that rhythm and we had to find, in a very close percentage, the proximity of where the final movie was going to be, kind of at the moment that that was being shot, this was a very different thing.

Colour Grading The Revenant

In this Variety Artisans they create a composite episode on interview-shy Director of Photography Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki. It should be noted that Chivo has won that last two Oscars for cinematography and is up for another with The Revenant. What’s interesting about this episode is that it is colorist Steven J. Scott who largely speaks on his behalf. It’s also great to hear from some of the industries best DoP’s on what they make of his work.

It was a really new way of working, it wasn’t like he shot some stuff, and didn’t know what he was going to do with it, he had actually planned it out quite brilliantly… I think it’s that love of very intimate details and moments, that makes the movie come alive. It’s saying there is more than the simple narrative I’m presenting. – Steven J Scott

There are also a few tid-bits on the colour correction workflow in this Studio Daily interview with Editor Stephen Mirrione.

The dailies come to me with a base color on them, supervised by Chivo and Alejandro while they’re shooting. While I’m working on it, if Alejandro wants to make a slight change and it’s something I can do in the Avid, I’ll do that, rather then sending it out to have it redone. But yes, sound started working early, VFX was working early and constantly, and we started color timing back in June, when Chivo and the colorist were working on a far-from-locked version of the movie. There was a lot they wanted to be able to do to fine-tune what the frame looked like.

UPDATE: Technicolor Case Study

Technicolor, the finishing house used by the team to deliver the film, detail the complex hand drawn and animated matte work used to shape the film’s final look, in this 3 page PDF case study that you can download from the Technicolor site. Thanks to the excellent and free, Tao of Color Newsletter for the find!

A team of finishing artists under Scott’s supervision color graded the imagery using Lustre 2015 Extension 3 software and a Christie 4220 4k projector. Simultaneously, a team of 10 visual effects artists under Spilatro’s supervision worked to hand-animate mattes and use them to perform roto work on faces, bodies, and other elements photographed by Lubezki in order to assure that directional key light, backlight, or shadows were hitting exactly where Lubezki wanted them to hit, and moving correctly with corresponding body parts or elements in a natural way so that viewers would be unable to detect any manipulation had ever occurred.

UPDATE – NAB 2016 Presentation

In this excellent presentation by Technicolor’s Steve Scott, you can learn a lot more about the incredibly detailed colour grading work performed on the film using Autodesk’s Flame Premium and Lustre. This discussion over on Lift Gamma Gain has some great insights on the seminar too.

Sound Design on The Revenant

The always excellent Soundworks Collection has a great collection of interviews from re-recording mixer Randy Thom and sound designer Martín Hernández on their philosophy and process in bringing the audio side of the film to life.

For me there are wonderful spaces where there is very little dialogue, where the landscape and nature really does become a character in this movie. And Alejandro opened the door for that to happen, and likewise there are purely music moments, where you hear very little in the way of sound design or sound effects. And there are some great places where you are hearing sound design and music and you can’t tell the difference between the two. – Randy Thom

Normally the Soundworks Collection videos are embeddable so hopefully they’ll fix this setting soon, but in the mean time jump to watching it on Vimeo.

There’s a really brilliant write up over on Pro Video Coalition from Woody Woodhall about the complex and elaborate work that went into creating a soundscape that would multiply the impact of the spectacular images on screen.

The challenge for Alejandro was that he found that some approaches to sound editing can be very illustrative. Like, you see the tree moving, and you put the tree sound in. He was trying to get away from that. It’s not just including the right sounds that you see, but it’s adding the sounds that you do not see.

When the sound belongs to the picture it’s not because it’s illustrating what’s there, it’s because it has the genetics of the image, which is a very different thing. If you want to try to transmit the loneliness and the vast size of nature, those are subjective things. The loneliness and the coldness and, you know, all these things that are happening in our brains when we’re watching a film, they happen because of other very subjective elements. Sound should help tell that, very subjective, part of the story. – Martin Hernandez

UPDATE: Sound Mixer Interview

Studio Daily is producing some really nice Oscar nomination coverage, which includes this interview with sound mixers Frank Montano and Jon Taylor, which features a few great insights on the challenges of mixing such an epic and intricate project. A great read!

Think haunting, elegant, aggressive,” Iñárritu told them when they first planned their approach. “Haunting, meaning that you should never should feel safe when you’re walking through the forest or through the snow,” says Taylor. “Figuring that out is very, very difficult. It can’t be haunting like a scary movie, where you almost play nothing — the absence of sound is scary as hell. But nature has to live wild in this film. And Alejandro picks up on even the slightest hint of anything fake or unnatural really quickly.”

The Revenant‘s original mix was done in 8-channel 7.1 surround to best bring as much of the outdoors in to the movie house. “This also gives you a left and right mid-wall surround in the theatre,” says Montaño. “The format lends itself to an immersive feeling. But couple that with Alejandro’s and Chivo’s camera work with all the movement, which really amplified our contribution to the film, and we knew we had to keep moving the sound continuously. Everything, from dialog to sound effects, were in constant motion, prelapping and transitioning throughout the entire film. It gave you the quality of being in the movie, not just watching it.

UPDATE August 2016

Check out the full presentation from the Avid booth at NAB 2016 with Martin Hernandez in the video above and the supporting blog post on the Avid site here.

We wanted to keep the sound as real as possible—and at the same time unreal. It’s a very interesting and challenging process to see how much of the real world leaks into the dream world, and how much of the dream world leaks into reality. The Revenant happens in a world that has no reference to our own. Our geographical references are buildings, lights, and cars. But if you stayed in the woods for a year, those references vanish. They lived in a completely different world sound wise as well. It was a process to understand that we were in a completely different world, seeing it through the eyes of the main character.

The Revenant Visual Effects

For a film that aims to be as natural as possible, there are still a boat load of ‘concealed’ visual effects in the film. In this excellent interview from Studio Daily you can hear from ILM’s Richard McBride, overall VFX Supervisor, on the detailed efforts, and re-work, that went into creating Alejandro’s vision. The film’s most talked about scene is obviously the bear attack, but numerous scenes involved animals that were entirely computer generated.

Were there technical challenges with the bear?

The fur. Fur is always a challenge, especially seeing it that close. It has some wetness. There’s a lot of debris caught in it. So we had a lot of artistic detailing and nuance. The bear team studied and matched reference and looked at the environment. They had to mix in blood and wetness from the rainfall. It definitely pushed the pipeline at ILM quite a bit. We discovered some new techniques for creating a detailed groom and translating that into the motion and simulation of the fur. For the bear, we had multiple levels of simulation — skeleton, muscles, fascia, skin, fur. We’re not as close to the bison and wolves, so creating their fur was simpler, but we still had the combination of muscle, skin, and fur simulations.