How to Edit an Independent Feature Film – Interview with Julia Bloch

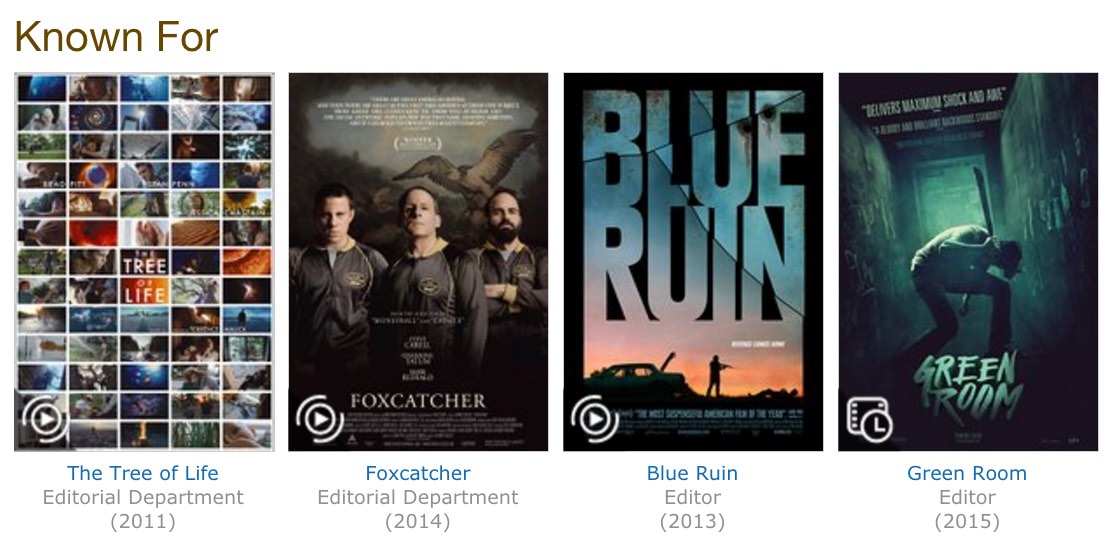

How did editor Julia Bloch go from an obscure film school in Denmark, to playing doubles tennis with Lars von Trier, to being credited an associate editor on Tree of Life with Terrence Malick, to having her second feature film, Blue Ruin, premiere and win awards at the prestigious Cannes film festival?

In chatting with Julia it is immediately obvious that her warmth, wit and wisdom has served her well in the personality driven world of the edit suite, and it also means she’s an ideal mentor for any editor looking to hone their craft, to learn from.

In this extended interview you can glean a huge number of insights from Julia on how she broke into the film industry, networked, created opportunities and established herself as a successful indie feature film editor.

You can also learn a lot about:

- the craft of editing

- what makes it unique as an art form

- the smartest way to build a first assembly

- why it’s crucial for directors to watch their own dailies

- how to approach a scene for the first time

- when to stop changing things

- managing test screenings

- using temp music

- attending film festivals and much more!

Take the time to walk through this conversation as it will be an educational and illuminating journey!

Interview with Julia Bloch – Independent Feature Film Editor

After graduating from Columbia University with a degree in Comparative Literature she began working in an art gallery in NY, which showcased the work of several prominent video artists.

Inspired by this and looking to try her hand at something new she ended up going to a film school in Denmark called The European Film College, not too long after the impact of Dogma 95 was still being felt on the continent’s filmmakers.

It was an intensive one-year course that was pretty practical in nature with students experiencing a basic level of training in everything, which is where she discovered her love for editing.

“I did the editing module pretty early on and it really clicked with me, I think because I had a background in literature. I discovered that once you get into the edit suite, it is very much like writing; there is a grammatical structure to the way you put things together.”

Without any contacts in the U.S. film industry Julia decided to moved to Copenhagen and managed to get a job as an assistant editor at Zentropa, Lars von Trier’s film studio.

It was like an anarchist’s, crazy weird studio, but still a studio. They had their own editing department with 5-6 basically full-time editors doing features, documentaries, commercials, music videos etc. They had built their own machine room and their own system for doing things – it was all Avid based – so it was pretty streamlined.

I worked for about a year and a half as an assistant editor on 3-4 different feature films and various other things while I was there and because it’s a studio with all these facilities, and because everyone who worked there was really cool, they kind of let us assistants have the run of the place in the off hours.

So I was able to edit a few short films for friends on nights and weekends because I had access to the edit facilities, and that was awesome.

After moving back to the U.S., albeit with a much fuller resume of feature credits, she soon realised she had to start over in the very different system of the N.Y. film scene.

I had to figure out networking and the unions and how to get a job, so I had to start from the ground up again. Getting coffee with anyone I could, you know – my mother’s neighbour’s son is a producer and maybe he’ll have coffee with me!

Did you have a plan for breaking into the US industry?

[Zentropa > first U.S. assisting job > Tree of Life > first U.S. Feature break > Sundance Labs Fellowship> Blue Ruin]

I did not have a plan!

You can always look at things retrospectively and say this led to that, but when you’re in it, it doesn’t feel that way.

I suppose I was a little bit influenced by the fact of having started my career in Denmark – it’s a social democracy, or at least it was when I was living there, so it’s a very anti-hierarchical society in general.

And Zentropa in particular was a very unconventional place to work. Everyone ate lunch together in this big common area. So on any given day you could be sitting down to lunch next to big producers like Sisse Graum Jørgensen, but also a famous Danish actor, the maintenance man, and all the interns are at the same table.

I was the assistant editor on one of Lars’s films, and his editor – Molly Stensgaard, a woman I admire immensely – she’d say “Oh we’re going to play tennis on Friday, would you care to join us?” – there was a tennis court at Zentropa, so this would be part of the work day – and the next thing I knew I’d be playing a double’s game with Lars and his editor and the post-production supervisor… it was just crazy.

But then when I got back to New York, it was like – you can’t just call somebody up. You have to go through their agent or this or that person.

But because of my experience in Denmark, I knew that people aren’t totally inaccessible, which really helped give me some confidence to try things others might not.

So my plan, if I had one, was to be an assistant editor for a while on pretty ‘good’ films. Or at least ambitious films with interesting editors and other people I could keep learning from. And meanwhile to just try to keep cutting things on the side, as I had been in Demark, because I knew people were going to ask to see samples of my work.

Plus I knew enough to know assistant editing is a completely different job to editing and one thing wouldn’t necessarily lead to the other.

> first U.S. assisting job >

One of the people I’d met in my prolific coffee season was this really nice guy who was an assistant editor who had worked on some really cool films, but when I met him he was unemployed and was like “I wish I could help you, but…”

Then three months later, he got a pretty big job as a first assistant editor on a studio film and was looking for a second, and asked if I was interested.

That was a huge break for me, because it got me into the union and it was one of those big 6-7 month long jobs. It was a hard job, but I got to see the whole cutting room experience – dailies, lab processing, how an assembly gets cut, watch the editor and the director interact, how to deal with the studio executives, and producer’s notes and all that stuff.

But meanwhile I was thinking – I need to keep editing! How am I going to do this?

> Tree of Life >

So I asked myself – who are the directors that I want to work with? Even if, just as an assistant. Who are the people that I admire and I want to learn from? Well…why not start at the top of your list?!

I had seen on IMDB that Terrence Malick was in production on Tree of Life – and honestly I just cold called – well, cold emailed – Sarah Green, one of the producers, and gave her my whole spiel.

I went back and forth with her assistant for a while, and then it turned out I had a friend in Texas who knew somebody – so I was really working all these angles. Then one day, I was sitting at my desk on this assistant editing job – going through stock footage or whatever – and I got a phone call and it was Terrence Malick!

He wanted to talk to me about potentially coming down to work on Tree of Life. I was really trying to play it cool on the phone and not hyperventilate.

That was obviously a very unusual opportunity and I went down to Austin, to meet him and his team – there were several editors working on it. Tree of Life was in post-production for about 2+ years and so when I came in it had already been underway for a while.

It was so collaborative – there was never just one editor on at a time, and so even in a junior position I had the rare opportunity of working with all these incredibly experienced and talented editors who were there.

Terry has this system of using a lot of junior editorial people who really get involved in the process in a meaningful way, so I ended up with an associate editor credit on that film.

It was absolutely the most exhilarating creative experience I’d ever had. Terrifying and frustrating and crazy-making also, it was wild. Tree of Life was an experience where I felt like I was really involved in a purely creative process.

Initially I went down for a couple of months but it kept extending and in the end I was in Texas for a full year.

It’s hard to use that as an example of breaking into the US film industry though, as it was such a unique experience, except that it got me to the place where I really started to see the potential for editing as very engaging and deeply creative, satisfying work.

But I still hadn’t had the experience of being the sole editor responsible for the entire film from beginning to end. So I came back to New York and did a couple more assistant jobs to keep working, while looking for a chance at doing my first feature.

That took a long time, because people could see I’d done this thing with Terrence Malick and that’s amazing, but there’s like 6 credited editors… and they’d say “That’s great, but you still haven’t cut your first feature, as the sole editor.”

> first U.S. feature >

That was a real hurdle for me, but I finally met a director who was willing to take a chance on working with me – Tom Gilroy. He was the director of The Cold Lands, which was my first official feature.

We didn’t have the budget for an assistant so I was able to use all my training to sync the dailies, make sure all the footage was organised correctly and so on. It was really useful that I had that background, but being responsible for both sides and switching between the more administrative and creative tasks was a challenge…

But it was so satisfying to have taken the film from dailies all the way through the mix for the first time. I learned so much on that job, from the director, Tom, as well as the producers and everyone involved.

The production company behind it, Cinereach, are great New York film people so that opened up my world a little bit. They were all incredibly supportive and I got a great window into the New York film scene through them and through Tom.

> Sundance Labs >

The other thing that happened was that, the summer before, the Sundance Institute started an editing fellowship – The Sally Menke Memorial Editing Fellowship – and I was the inaugural recipient in 2011.

I went up to the Sundance Labs that summer, which was a fantastic experience, and got to be immersed in the whole Sundance experience.

Part of the fellowship includes time with editing mentors whom I met with on a regular basis throughout the year. It was that fall (autumn) when I started The Cold Lands so I had this great support system where I could send cuts to my mentors and ask their advice on anything, from how to talk to the director to how do you know when a scene is finished?

By the time I finished The Cold Lands, which was a tiny, low-budget, non-union film, I needed to take another assistant job for the money. I spent a couple of years of doing that – back and forth between editing and assisting.

> Blue Ruin >

At some point, when I was working as an assistant editor again, I was contacted by Anish Savjani from Film Science, as he was starting to work with Jeremy Saulnier on Blue Ruin.

They had gotten my name through a producer (Matt Parker) who had contacted me as an editor for a short film he was producing that I didn’t end up doing, but at some point in our email conversation I had given him my phone number and he saw that my area code is from Nashville – I’m from Nashville, Tennessee originally – and so he wrote me again;

“I’m from Nashville, you’re from Nashville – let’s get coffee!”

We met up for coffee and as we were leaving he said

“My buddy Rich Peete is producing this film – the director is really talented but it’s kind of out there. It’s a murder/horror/comedy thing – I don’t know if it’s really your style, but they’re looking for an editor.”

And I thought that does not sound like my style, but I do want to edit another movie.

A few days later, Rich Peete (who was working with Anish) emailed me and the way he presented it was like “Jeremy Saulnier is writing and directing the script, he’s also going to be shooting it himself – but don’t worry it’s not as bad as it sounds!”

https://vimeo.com/45131708

But they also sent me a camera test they’d done, that was really cool that had Macon (Blair) in his full bearded look and they shot it on the boardwalk down in Delaware with cool music and I thought – ‘Oh that’s not really what I had in mind when they said horror/murder/comedy genre.’

I watched Murder Party, Jeremy’s first feature film and a short film he had done a while ago, and it’s true that these are not the kind of films that I would gravitate towards myself, but I could tell they were really well done. That there was a real style to them, an energy.

So I thought – ‘OK what the hell’. I read the script, and at this point I had read quite a few scripts, and the script for Blue Ruin really stood out.

It was so well written and Jeremy also being a cinematographer, he included a lot of the visual stuff exactly as it appears in the movie. The script was incredibly detailed and nuanced and it was exciting to get a script like that.

When I met him and his producer Anish, they were great. Jeremy knew that I had gotten the Sundance fellowship, that I had worked with Terrence Malick and had this background in Scandinavian film – and he was really interested in the fact that we had such different influences.

That really appealed to me – that he did not necessarily want to work with an editor who had cut a bunch of horror films already, or was a total gore nerd or something. He said he was looking for a counter-point to his own genre tendencies, and he thought the film needed that.

I was really hesitant to take the job, because I didn’t see myself going in this direction, but I really liked Jeremy and in the end I just thought – maybe this will be fun! It was so different than anything I’d ever done. And of course, it turned out to be my breakout film.

What is the like working on an indie feature film where the filmmaker has written, directed, shot and re-mortgaged his house and invested his wife’s pension into making the film?

Well, obviously the personal stakes were really high for Jeremy, so there was a certain amount of stress that comes with that. I felt a lot of responsibility. But also, as you start working on something that you realize is actually going to be pretty good, you just want to make it the best version of itself that it can be, no matter what.

The shoot was very carefully planned, and because Jeremy had a lot of experience as a cinematographer and he was shooting it himself, it was very streamlined as he knew exactly what he wanted to get.

The coverage was very specific – it’s not the kind of film where you’re going to do a lot of structural work. First the guy has his head blown off and then you put the body in the trunk. You’re not going to start pulling scenes from the third act to clarify something in the middle of the film.

I have worked on films that are more non-linear where a lot of the heavy lifting is around “Should we have these characters meet in scene 30 as it’s written, or would it make more sense, if we put this other scene earlier, because we need to establish that they know each other.” Or even to the extent of “Should we have the Mom come back or not…?”.

You can do those things in other films, but in Blue Ruin the editorial work was really selecting for performance and pacing. The idea of shaving frames and sometimes more, but getting to the exact point where you want to leave one idea and get to the next.

I just taught an editing class for the first time, which is when I realised what an internal process this is for me when I’m working. I can mentally make 25 different decisions about why I should do this or that before making a cut, but when you stop and try to articulate it to a room full of students, all of a sudden it sounds so boring and tedious! And I was struggling to try to explain why this is so interesting!

Editing is a lot about thought. What I think is so fascinating and exciting and effective about editing as a tool is the idea that you create when you make an association or juxtaposition between two images.

When you have these two clips that you’re putting together and then there’s that third thing – the thing that happens in your brain when you connect A to B – and what that represents to me is thought. We call it a cut, but actually it’s a connection.

Andrew Stanton, a director at Pixar, says that you should give the audience 2+2, but you shouldn’t give them 2+2=4, because they’ll work it out themselves. That’s how they participate.

Yeah and in that gap, that’s the thought. To a certain extent you can control the audience’s access to information and emotion, but you can’t control what their reactions are going to be. I can’t guarantee that someone else is going to find this funny, but I can present a situation as comical.

What is your editorial process?

// Watching dailies // building a first assembly // spotting problems // directors and dailies

My process is pretty straight forward, depending on how much time there is and whether you have an assistant, but let’s say you’ve gotten to the point where the dailies are sorted and the sound is synched and everything is organised and you’re actually ready to start cutting.

If I’m on a film while they are shooting, which is what I prefer, then you’re getting the scenes a day or two after they’ve shot them and they’re all out of script order of course, because they’re shooting according to location or actors’ schedules or what-have-you.

I’ve read the script, so I know what these scenes might represent in terms of the overall story, but I also know that might shift. We might not use the scene or move it into a different place.

Maybe as it’s written it calls for the character to be really happy but we might find it interesting, after 4 months of working on the cut, that maybe she’s really nervous instead.

So the idea of what’s the best take or what’s the best way to cut a scene isn’t really relevant to me in the beginning, because I don’t really know, yet, what I want out of that scene.

This means my first pass is really about watching the dailies for myself and figuring out what are some of the options and learning the performances.

My first response to the performance is pretty important for me to hold on to, and it’s easy to get blinded to that as you go over and over the material, so sometimes I’ll take notes.

My first pass is focused on trying to pick out the best or strongest performances overall with clean camera moves and stuff like that. I think of it as a glorified way of watching dailies, and so I try to use at least one shot from every set up so I can look through a scene and remember ‘oh yeah there’s a wide and there’s this and there’s that’.

I’ll keep in every line of dialogue and I keep it in script order because I know the director is going to want to see that version and it’s useful to have a foundation that you can always go back to, that represents the complete initial idea.

I’ll work this first assembly until it’s basically good enough so that I wouldn’t be terribly embarrassed if the director walked in tomorrow, but generally they’re on set and I’m working remotely.

But I’m also trying to keep up to camera so I’m not going to let myself get obsessive and spend too much time on this one scene because I know I have five more scenes coming in tomorrow.

I might try and put in some music, if it really needs it. But I keep it very basic, and then keep going, keep going until I reach the end.

I’ll then ask for a week after they wrap the shoot to finish my assembly because I’ll finally have all the material and I can watch the whole thing through for the first time.

This lets me see the holes or what isn’t working or that I have to remember to show that he buys the milk in that scene, because he’s going to pour the milk down the drain later – or whatever.

There are things that might not seem that important to you in the individual scenes, but then you realise you do need to show that, because of this.

At that point I try to pull it together and make it as presentable as possible but without going too far down a specific path because that may not be what the director has in mind.

Once you start working with the director, then the film takes its own shape. But the other thing that I think is important, and that I always talk about with the director is, when are they going to watch the dailies?

On these fast-moving, low-budget productions, they often don’t have time at the end of the day to watch the dailies properly. a) They’re exhausted and b) they have to prep for the next day’s shoot. So they don’t have any time or energy to go through what they’ve shot in a methodical way.

This means by the time we sit down to work together I’ve watched all the dailies really methodically and have a sense of all the coverage and they’re like “I think we got that…” or they have this really specific idea about…

“That day, we got this amazing crane shot and we have to use it!” and you’re like – actually I don’t think you got the crane shot, or, ‘it was out of focus!’

In an ideal world, I would sit with the director and watch through all the dailies together so I could make notes and talk about the performances and we could be on the same page. That would be great, but it doesn’t usually work out that way.

I think it’s important for the director, to build that into the schedule. That at some point, probably after they wrap, that they will sit down and really go through the dailies, if not with the editor, at least on their own, to get a good sense of what they actually have.

Talking about presenting cuts, do you prefer to cut without music, with it? Do you add your own sound design? Some editors talk about trying to get things to a near perfect level, all the time?

I think it depends on what stage of the process you are at and what level of project it is.

I’ve not worked on a really fancy movie where I have to show a rough cut to a producer and they may or may not fire me based on whether it’s working or not. That’s a reality that I haven’t had to deal with yet.

In my world, when I say the cut’s ‘good enough’, it has to convey the ideas. It might not be fully realised, it might not be the best version of that, but you get the ideas.

That might mean let’s hold on her face the entire time the other guy is talking because that’s a concept. What if we don’t cut round back to the guy while he’s talking, because her expression and reactions are so interesting?

You know maybe this isn’t the best take for that yet, but this is the idea, and the audience will get the idea when they watch the scene.

I always watch it myself, before I show it to the director, imagining they are sitting next to me, so I can ask myself ‘am I cringing right now?’ and if I’m having that inner dialogue, then I fix it.

In a rough cut, if I’m watching it and I think ‘OK, it’s not perfect, but it gets the idea across’ then I leave it because I might not be sure how fully committed to the idea I am or what the director is going to think yet.

I don’t want to “paint the trim on a tear down”, as they say. On the other hand, if it’s for a screening and we’re looking for audience feedback, I’ll be more rigorous, because you have to know exactly what it is you’re testing.

As far as I understand it an early cut of Blue Ruin was submitted to Sundance, but wasn’t accepted.

Then you paused post-production for a time and then later submitted it to Cannes where it was accepted. What changed in between?

The submission to Sundance was a ridiculous thing really. There wasn’t enough time. There was the default indie thought, ‘we should submit to Sundance,’ but everybody knew it was a crazy idea.

By the time they finished shooting Blue Ruin, Jeremy and I only had about two weeks to work together before the Sundance submission deadline. Which is insane. It wasn’t something that was ready to be seen. It didn’t convey the feeling of the film.

But I guess that’s just a choice that people make at some level. Maybe if we didn’t submit it you’d always be wondering – what if we had? But it was very understandable that Sundance passed on that version.

When a festival rejects a film based on a rough cut, it also means – will you even be able to pull this off if it is accepted? You only have two more months between submission and the festival to finish the film.

So even if we had worked on it every single day I don’t think the film would have gotten to the right place, with music and all the finishing details, in time to screen at Sundance.

I forget the exact timeline, but we had to go dark for a while because we ran out of money and Jeremy had some personal stuff going on. As I recall we went on hiatus, then came back and worked on it to get it cleaned up, and in a kind of ‘why not/long shot’ let’s-just-submit-to-Cannes-and-see-what-happens kind of way, we sent it to Cannes.

When it got accepted – which nobody expected – then it was like “Oh shit, we have to finish this film in four weeks!” But, by that point, the film was very close.

All the pieces were there but we needed to tighten it and do all those tiny tweaks that, at the end, can really elevate it. We were working with the composers at that point too, so those final four weeks were very intense polishing.

Just to thread back round to Terrence Malick and Lars von Trier – are there things you learned in those experiences that came into play on Blue Ruin or the films you’re cutting now? How has that shaped how you edit?

That’s a good question, because I do think working with those exceptional directors early on influences what I do now.

I mean, I really wasn’t in a creative position with Lars, I was an assistant, but I was working with his editor Molly, and I had a lot of access to their creative process.

One of the things she taught me was to be bold and to make strong decisions. Taking a certain tack. Again, you need to convey a specific idea – you may not end up with that idea, or the director might change the idea – but whatever it is that you want to do, know what that is, and try to achieve it.

It can be overwhelming when you begin. You have all this footage, and it can feel like ‘I don’t know where to start, what am I even looking for?’

Simply making a decision – what’s this scene about? The dialogue. OK, so right now I’m just going to stick with conventional coverage. That mentality has been really helpful to cut through the noise and just be productive!

Of course Lars is an incredibly bold filmmaker, he takes such huge risks and is constantly experimenting. It was inspirational to observe him at work, always questioning what the cinematic form is, pushing the medium: how can we use it differently than what is expected?

And then in working with Terry (Malick) I feel like that’s the experience that gave me a sense of the infinite possibility. You can do anything you want. You can create worlds, or entire subplots that don’t really exist by focusing on certain glances between two characters, where you’re creating these suggestions. He is a true artist in that way, and I learned to see editing in that light by working with him.

But on the flip side, I also learned that, at some point, it’s important to be able to ask “when are we really making it better, instead of just changing things.” Being able to hold onto something that works and build on that, and not just constantly re-evaluating everything.

I try to hold on to that in the edit room when we’re saying “We could do this, we could do that…” and I think, yeah but this is working.

I give the example of when you’re making your bed. You’ve got to tuck in one corner of the sheet! (laughs) You’ve got to at least have one corner tucked in to have something to pull against, otherwise you’re just moving the sheet around.

So as an editor it’s important to have a voice and to bring that voice to the scene. It’s also important to know when to stop.

One of my favourite anecdotes on this is of a primary school art teacher whose students always produce amazing work and when asked how she does it she said “I know when to take the paper away.”

Yeah, although there’s still an element where I’m not going to tell Terrence Malick what to do, I’m going to follow his lead on this one! (laughs)

Sometimes it’s hard to find the right balance between too much and too little. Sometimes it’s as much about what you take out, as what you leave in. I cut a film last year called In The Radiant City, which is a story that doesn’t revolve so much around tension and plot, it’s a lot more about emotional development and psychological development and family dynamics.

Which is challenging material for me to work with. I feel like a lot of other editors probably cut their teeth on something like that, but I’ve never done anything like that before, so it was new for me.

On that film one of the challenges for the director Rachel Lambert and me, revolved around something that came out during the screening process.

There’s an element of crime in the film that happened in the past, and we were leaving that part pretty vague because we didn’t want the crime itself to be the focus of the story. That’s not the point, the story is about the life of these brothers as a result of this thing that happened 20 years ago.

But we found when we were doing screenings that by leaving it vague, the audience didn’t have enough information.

We kept alluding to this thing, but not really explaining what had happened and so the whole time the audience was asking – why is the brother in jail, what happened?

They were pretty distracted by trying to figure out the procedural aspect of “what was the crime?” And we’re thinking ‘No, no, no you’re not supposed to focus on that!’

Counter-intuitively, what we found was that if we don’t want them to focus on it that much, we have to give them more information. So we added a couple of lines of ADR to fix it.

There’s one scene in the lawyer’s office where it all comes out – sort of organically because you’re in the lawyer’s office and he’s talking about the court case, which is the only scene in the movie which addresses head on this situation so we added a very expositional line like “Michael’s serving time for….”

I was worried it was so obvious! But actually, once that was satisfied, we were able to get the audience to focus on what we wanted them to focus on, which was this more nuanced relationship between the brothers and the idea of, how does the past come back to haunt us?

That was a great learning experience.

How do you pick the directors you work with?

Even five years ago, I just wanted to get a feature film credit under my belt. But I’d seen enough from my assistant days to know it is a lot of work. It’s a long time commitment and you invest a lot in it.

The biggest factor for me in deciding to work with a certain director is do we connect on a creative level – are we on the same page? That doesn’t always mean we have the exact same references or background – Jeremy and I come from very different worlds in some ways, but we are completely in sync when we’re working together.

I didn’t really know what I was getting into when we first met about Blue Ruin, but I knew that I liked him and that we had an easy rapport, I could tell from our first interview that he was someone I wanted work with.

When Rachel and I first met, it was also an instant connection. We just clicked creatively and were easily communicating right away. I should say that that doesn’t actually happen with me that often, so I’m quick to recognize it when it does!

Obviously, I also need to feel I respond to the material in some way, because that’s what you’ll be working with.

You’ve just cut Jeremy’s second feature film, Green Room. Is it helpful to work with the same director again, given all the millage and understanding you’ve built in your working relationship from the first time?

Definitely. Jeremy and I just really clicked on Blue Ruin, so I knew I wanted to work with him again. He’s so precise and specific about what he’s trying to achieve, there’s something very satisfying about that. Even though both films’ subject matter is super dark, we actually had a lot of fun working on them together.

I knew Green Room was going to be on a bigger scale with more actors, more action, bigger theatrics and logistics etc. so I thought it would be a fun challenge to take my work up a notch in that way, technically speaking.

I definitely had more confidence going into it because I had worked with Jeremy before and I knew his style of working and it definitely makes the whole process smoother because you already have a shared language and you know each other – so there’s not that initial awkwardness.

I mean there was stress for other reasons, but I knew going into it that it would be a really positive work experience.

That’s a really smart way to think about it.

Just diving into talking about other departments and collaborators. For example Blue Ruin had such a subtle sound design/music score.

What’s your approach to collaborating with other departments on an indie feature.

On Blue Ruin and Green Room it was quite specific. On Blue Ruin I tried using a temp score and I used a piece from Michael Clayton in the shoot-out scene and I’m thinking it’s in just to give some rhythm while we’re working. But that didn’t go over very well.

Jeremy was like “That’s Michael Clayton.” (laughs)

But that’s something I would normally do – use temp scores from other films or from a library of music I’ve built up from other composers I know or have worked with before, so that it’s not all well-known Hollywood music.

But Jeremy was very specific about the sound he wanted to create in an understated way, and he knew he wanted to use Will and Brooke Blair, who happen to be Macon’s brothers.

From the beginning Jeremy knew they were going to do the score because they had a shared sensibility on the project. The Blue Ruin score is all synth really, so they were able to play with some more ‘sound-design’ style elements, like drones, hits and zings and give us a whole folder of things to play with.

In Blue Ruin not a lot happens for long periods of time, and then all of a sudden a lot happens. And so it helps to be able to use those sound elements in the scenes for emphasis, to maintain the tension.

So we would add them in and then hand it off to the composers and they would work on the musicality of it. But it all happened quite late in the game to be honest.

Green Room was different because there are some live music pieces in there. Luckily it’s punk rock so they’re all flailing all over the place so it didn’t have to be super tight to the music (laughs) but they are singing so it does have to be in sync!

It takes place in a music venue so there’s constantly loud music playing through the speakers. So we really had to think about how is the score going to interact with the hard-core source music that’s always playing in the background. We were able to work with Will and Brooke much earlier in the editing process and that was really helpful, because there are some really subtle things going on with the score that help to define and sustain the tension throughout the film.

A scene has to work without music, but you want to get it to the place where when you do add music, it really elevates it.

Working with sound designers at the end is a huge part of the process, and it’s a lot of fun for me because I get to sit back on the couch and watch others work.

“Yeah let’s bring in the bass on that!” (laughs)

But for timing, pace and mood I try to do a lot of that work myself early on. Even if it’s just because you’re submitting to a festival before you’ve had time to do your final mix, or just for internal screenings – the scene always has to work. So if it revolves around someone knocking at the door, you need to put in the sound effect of someone knocking at the door!

Music is a little bit less necessary, narratively speaking, but it can really make the difference tonally. I guess my taste, such as it is, would be to be sparing with music but to really experiment with it.

Are there a lot of VFX shots in Green Room? Were you temping those in or did you have an assistant for that?

Green Room is the first movie I’ve done where I had a legitimate, highly experienced assistant editor, Kathryn Schubert who was awesome. She was on the film all the way from the beginning to the end and she did a lot of temp work for us.

Jeremy is really committed to practical effects and special effects make up. So there definitely are visual effects in the film and they’re really important, but for the most part it’s clean up work.

There’s not a lot of green screen work or anything. We might enhance shots here and there, but it’s all designed to feel pretty natural.

On the topic of having an assistant, how does relationship work?

We interviewed four or five people and Kathryn had worked with a friend of mine who is a really experienced editor and he recommended her. She was the most experienced one of the bunch and we got along well.

That was the first time I’d had an assistant so that was another thing to navigate. Having spent some time as an assistant, I’m very sensitive to the dynamics in that relationship, and I don’t want to be overly demanding.

But at the same time there are times where you have to say, ‘No, I need it now.’ I’m lucky that I had some really good editor role models when I was assisting.

Having now experienced both sides of the relationship, what advice would you give to assistants on working with an editor?

When I was an assistant I was really hung up on my technical prowess. What if I don’t know After Effects well enough? Or will I really be able to do everything they’re asking of me?

And obviously raw technical skill is primary. But I think when I was an assistant I undervalued the importance of being an easy going, calm and confident personality. Because there’s a lot more pressure as an editor.

So when I was interviewing to hire an assistant, it’s not just ‘’are you a nice person?’ but the quality I’m looking for is a sense of resourcefulness.

If they don’t know the answer, they’ll go figure it out. Because not everyone is going to know every answer, and there’s always new things that come up.

If they’re too sure of themselves, that can be off-putting, more than someone who is humble enough to admit they don’t know it all but they’re confident they can work it out.

That, and bring a little humour and perspective to the edit suite.

You have to trust that that person has your back and that you won’t have to problem solve for them.

That’s great advice.

On the topic of film festivals, as an editor how often do you go along?

I love to go to the festivals, especially if it’s the premiere. It’s a really special time where you can celebrate the film and see it on a big screen with an audience who aren’t your friends and family. That’s so exciting.

It’s a great atmosphere to be around all those other filmmakers but I think its rare for an editor to go to festivals. It’s usually the director, producers and actors, sometimes Directors of Photography.

I’ve been lucky that the crews I’ve worked with have been pretty tight; I got to go to Berlin with The Cold Lands and I got to go to Cannes with Blue Ruin and Green Room.

Both times at Cannes, the producers rented an apartment and we had actors crashing on the floor, it was a lot of fun.

On Blue Ruin, one of the actresses (Amy Hargreaves) was there so she and I got to share a proper bedroom, as we were the only women. Otherwise there’s just a bunch of dudes everywhere.

If I have the time and I can afford the plane ticket, I’m always going to go because it’s also a great networking opportunity – I’ll be at Sundance and go to a party, and there are 10 people I kind of know from New York but I never see them and they’re all in the same room!

It sounds kind of schmoozy, but you’re not trying to work the crowd, you just get to put a face to name and have relaxed conversations in kind of an unguarded context. Maybe because people are drinking all the time! (laughs)

Last question, what do you prefer to cut on?

My school taught us Avid, so I learned how to edit on an Avid. To me that will always make sense to me and be the ‘best’, because it’s the most familiar to me.

I learned Final Cut 7 because I had to when I came back to the US, because that’s what people were using for low-budget stuff but as an assistant editor on feature films, everything was in Avid.

As an editor, because I prefer Avid, I will ask to use Avid, and there seems to be less of a stigma now around it – indie filmmakers used to think that it was inaccessible because it was so expensive and so they never learned how to use it.

I haven’t even learned Premiere, I mean maybe it’s a great program, but it doesn’t seem productive for me to spend my time learning a third editing software program at this point.

I’m not that interested in the deep technical stuff. Like, what’s the best codec for any given situation, or what’s the fastest system to export on… that’s not that interesting to me.

What’s useful to me as an editor, on the technical side, are things that let my hands go as fast as my thoughts. But I will also say I don’t think efficiency is always your friend.

Efficiency isn’t always your goal.

There’s something to be gained from trial and error and spending a little more time with something, rather than finding a technical shortcut to pass by all of the different steps to get somewhere.

What was really helpful was when I first learned how to do simple effects, like a split-screen or a re-size, because they increase the pool of usable shots.

I was an assistant editor on Foxcatcher (there were two editors working on it at the time, Stuart Levy and Conor O’Neill), and I would walk into Stuart’s room and he’d be doing these crazy split screen edits on a locked off shot, to craft the performances, to use the parts he liked from different takes.

I mean it’s a very basic thing, but it would never have occurred to me before seeing him do it. Your level of control and ability to expand the potential of the material – that’s what the technology should serve.

The technical details are really important but they’re only useful to me personally in the way that they expand the creative potential of the project.

Thanks Julia. That’s a really realistic way to look at it. The internet isn’t always as measured! I do agree – you can’t tell what something was cut on when you’re watching it, so a lot of it does come down to preference. Although personally, I’m just too much of a geek not to want to learn as much as I can about everything.

Thanks so much for giving me so much of your time and sharing your expertise!