Insights on Editing John Wick 2

For editor Evan Schiff, John Wick Chapter 2 represents his first major feature film as an editor, but it’s by no means his first time handling the pressure and prestige of a big budget action movie.

Having worked as an assistant editor for over 10 years, his feature credits include the first two (new) Star Trek films, Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, Warrior, Pan’s Labyrinth and many more.

It’s also not his first time cutting a full-on action movie, having previously edited the Salma Hayek action mayhem that is Everly.

Evan was generous enough to take the time to answer my questions on both moving up from an assistant to film editor (see this separate post for that!) and his experience editing John Wick 2.

In both interviews his answers are packed with expert insights you’ll want to take time to digest. This post covers topics such as:

- How to prepare for the job interview

- Cutting fast-paced, meticulous action sequences

- Handling the stress of a big budget movie

- Collaborating with the director

- Progressing as an editor in the industry

For even more insights on the editing of the film, check out this article from Evan, on the Avid Blog.

To begin a film of this size 11 days behind [camera], with a director and producers you’ve never worked for and who don’t know you, was stressful to say the least.

But as I sat in my new office scrolling through all the footage they had already shot, it became obvious quickly that I was about to be a part of something awesome.

Editing John Wick 2 and other Movies

How did you get the job editing John Wick 2?

I’m represented at UTA, and I got the interview for this job through my agent, Mike Rubi. They had already started shooting in NYC when the director, Chad Stahelski, called me for my first interview, and within a week or two afterwards I was on a plane to NYC to start work.

Once we got to know each other better, Chad revealed that one of the things that got me the job was my willingness in the interview to question some potential script problems I saw and talk through what solutions we might employ.

Bringing up script problems in an interview isn’t always the right choice, but in this case Chad valued the honesty and the insight, and it made all the difference.

How do you approach and prepare for that ‘first meeting’?

I always read through the script at least twice before the interview starts, since the second read often helps cement character names and plot points in my head for faster reference during conversation, and I tend to notice smaller details or connections in the script that weren’t obvious on a first pass through.

Once I’ve done that, I usually keep a text document with major themes I’ve picked up on, references to other movies that I think are useful for getting on the same page regarding editing style or story structure, and the basic details of the project as I know it (where it’s shooting, for how long, budget, etc.)

Lastly, I research the director, producers, writer, cinematographer, and actors, and note if there’s anyone else listed on IMDb that I’ve worked with before. If there are words or concepts in the script that are obscure or unfamiliar, I’ll research those, too.

And finally, if I have time, I’ll try to watch as many of the director’s previous films as possible, and any films that are explicitly or implicitly inspirational to the script, since those will often be a point of reference in the interview.

That’s the big list, at least. It’s often the case that interviews come together before you have time to do all of that, so in that case I cram as much research in as I can and just go for it.

Besides showing that you’ve done your homework, I think the other big component to a first meeting is revealing who you are and what your personality is.

Directors know they’re going to have to place a significant amount of trust in you to execute their vision, and they know they’re going to spend many hours with you in a small room doing it.

I think it’s important in the interview to show that you’re easy and fun to work with, you’re experienced and confident about getting the job done well, and that you are on the same page with them in terms of what they want the film to be.

How do you approach cutting an action scene?

Cutting action is certainly a skill, but a lot of it just comes down to feeling out the right timing.

As the editor you get the benefit that most action is shot in very short pieces, and without many takes per setup, so your choices in any given moment start off fairly limited, even if the sequence itself is long.

Since one of the things that resonated with audiences in the first John Wick was how clean and visible all the action was, we followed the same practice with John Wick 2.

Before I started cutting my first bit of action on this film, Chad and I discussed some general rules about staying on wider shots and holding on them longer than you see in many other action movies. This communicates to the audience that the action is real, that it is Keanu himself doing it, and that we are not hiding anything with fast edits and shaky camera work.

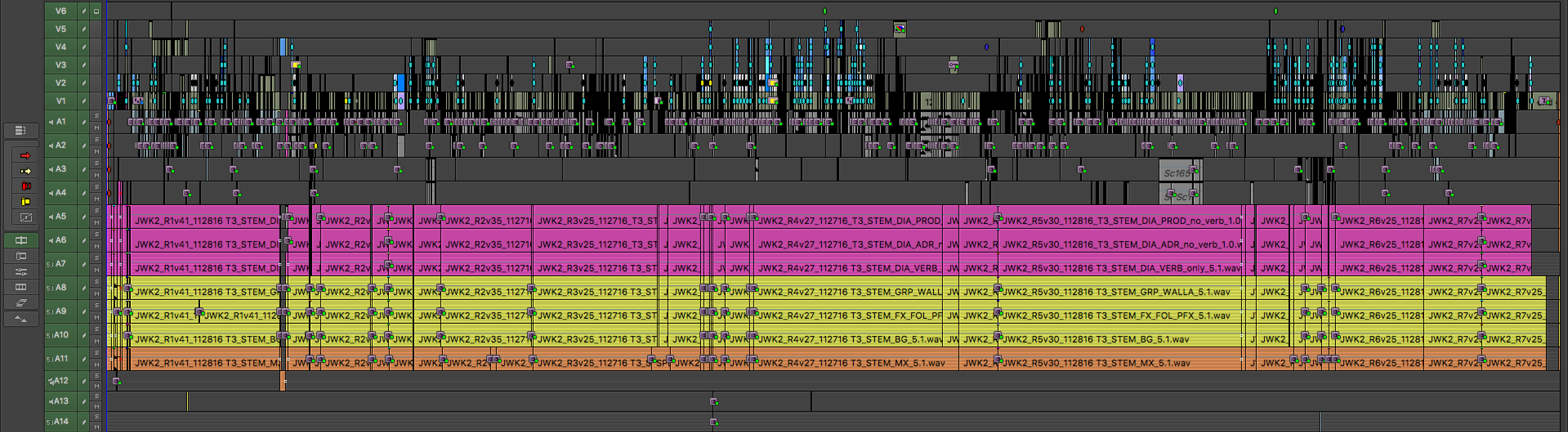

On this film, since Chad comes from a stunt background and has been hired as a 2nd Unit Director countless times to shoot big action scenes, we set him up with his own Avid and a copy of all the fight dailies.

He would then make his own assemblies of the fight scenes, we’d compare his version against mine, and then combine the best parts of both.

Since I don’t have that background that he does, he would go through all the takes and pick out very technical differences in the judo and jiu jitsu, and we would incorporate the best of those moments into the general structure I had already created.

It’s very important in a John Wick film to be spot on with your fight choreography and gun fu, so we always made sure that we found the best throw, the best movement, or the best reload and paired it with the best angle to see it from.

Most viewers won’t know all the detail work that Keanu is doing in all the fights, but for those with a martial arts background it should be very clear and very impressive.

How long does it take to cut a complex fight scene?

Not as long as you might think! Without going into specifics before the film is released, I’d say it took me 1-2 days of assembly per major fight sequence. Then in Post, Chad was doing his versions while I was working on other parts of the film, and when he was ready we spent maybe a week or two working together to refine all the fights. After that they were basically locked. We might have cut moments out if we needed to trim time, but we never broke open a fight and started again from scratch.

We do have a couple of car chases, and the bigger one of the two took a while to get right. There was a lot of footage and several gags that ultimately didn’t make the cut, so we were often going back to that sequence and experimenting with what should be in or out and what the structure should be.

Do you work with the rehearsal footage first?

Not on this film, but I have in the past. I think it’s useful to see the fight previs so you know how the whole fight is supposed to flow, but so many things change on the day they shoot it for real that there’s no substitute for working with the footage that’s actually going to be in the film.

What was the biggest surprise jumping to editor for the first time?

How exhausting it can be! I was used to working 12+ hours per day as an assistant like it’s no big deal, but when I jumped into the editor’s chair I was surprised at how tired I got after even 8 hours of cutting dailies.

All day you’re making a bunch of micro decisions on whether to use this take or that one, this angle or that one, this length or that one, so I find by the end of the day I’m pretty spent mentally.

What were the similarities and differences between cutting Southside with You and John Wick Chapter 2?

It was really fun to do those two films back to back, since they could not have been more different from each other.

Southside With You was all dialogue all the time, and since it was an indie with limited resources and only 16 shooting days, coverage was limited and any problems that came up during filming couldn’t always be fixed on the day.

Our biggest problem was building the right amount of conflict into a story where everyone knows the outcome, and doing it without having so much conflict that you wonder why they’re still on a date.

The director’s cut was 6 weeks instead of the usual 10, though that actually was enough time, and we picture locked a few days after we screened the director’s cut for the producers.

John Wick 2, on the other hand, shot for 45 days or so, and I know we would have welcomed several more days beyond that at least.

We had around 800 VFX shots, and a complex plot that required a lot of experimentation to convey correctly. Unlike Southside, we had the ability to fix some problems that we discovered or even created ourselves by moving some scenes around, but finding creative and achievable solutions to those problems was not always quick or easy.

We also found that it was difficult for other people to imagine how the action sequences would feel before we had final VFX in the cut, despite having temped everything including muzzle flashes and blood sprays, sfx, and using music from the first John Wick.

That introduced a bit of self-doubt about whether we should make changes to the action, but in the end we decided to believe in what we had done, and make changes only after assessing the cut with final vfx.

What are the challenges in cutting a lower budget film like SSWY?

The challenges of any lower budget film are usually about not having the resources you need to do the things you want.

Lots of lower budget films try to cut corners by doing things like laying off the assistant editor during Director’s Cut, or not hiring an assistant at all and requesting that the editor transcode and prep dailies as well as cut them.

If the producers of low-budget films aren’t that experienced, or they don’t hire a good Post Sup, you can get into a situation where they don’t save enough money to complete Post, and you end up not being able to get the DI, mix, or VFX quality that you want.

On Southside, I made having an assistant editor on the show a deal breaker. I knew they wanted to go to Sundance with a cut not too long after shooting finished, and I also knew from my own experience that it’s really difficult and straining to be your own assistant.

It requires you to put on your technical brain to transcode and organise footage first, and then immediately switch to your creative brain, look at the same footage from an entirely different perspective, and put a cut together in half the time you would have had otherwise.

It’s not a good way to work, it makes staying caught up to camera twice as hard, it’s not fair to the director that he doesn’t get a full day’s creative work out of you, and for all those reasons plus several more I felt it was better to be realistic about my requirements and risk losing the job than be too accommodating to the budget at my own expense.

How much of the temp sound design do you do?

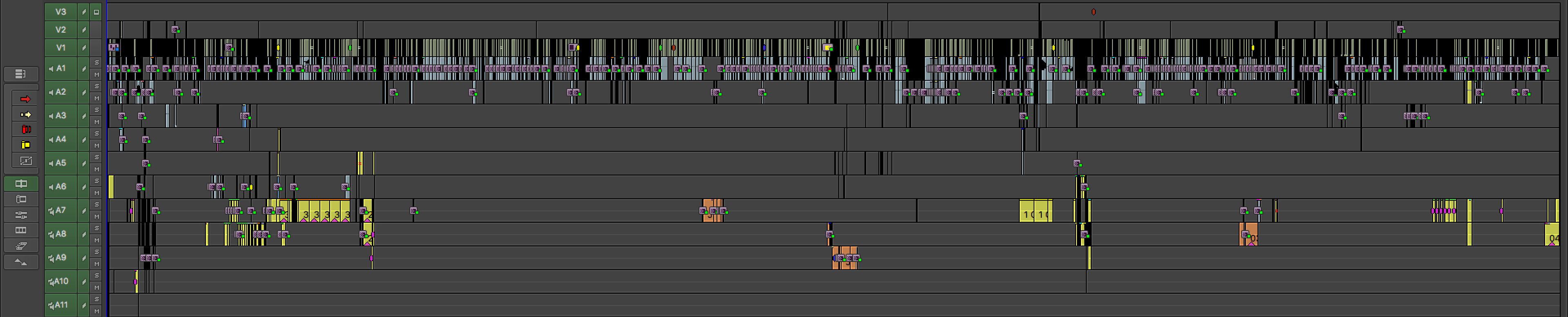

A lot. On a low budget indie I do almost all of my own sound and music editing, and temp VFX.

I’ll ask my assistant to hunt for sfx and music, and composite if they are comfortable doing that, but I like doing my own mixes and my own music editing. I guess some habits from my assistant editor days are hard to let go of!

On a bigger film like John Wick, my assistant did the majority of the temp sound editing, and was able to source some sound effects from our Supervising Sound Editor, Mark Stoeckinger. He would also do a rough mix of just the sfx, and I’d go through and fine tune everything including the music and dialogue.

On the music end, I found and edited temps for sequences where I needed music to cut with. These sequences were mostly montages or music-forward areas of the film. Once we had a music editor onboard, we had several spotting sessions with them to describe what we wanted the rest of the temp music to be, and they went to work.

We previewed John Wick 2 for a recruited audience twice. For the first preview, Mark and his crew at Formosa Group spent a few days mixing a hybrid version of our temp tracks and whatever sound work they had done to date.

We then got their 5.1 stems into the Avid (split out as dry dialogue; dialogue with reverb; group/walla; sfx & production fx; BGs; and music), and used those in our main reels.

I kept my dialogue tracks as they were and replaced everything else with the stems, so when it came time to do Preview 2 they were able to conform the ProTools session based on the edits in the Preview 1 stems, and then mix in any additional sfx or music that I had inserted between the two Preview dates.

Given your VFX background, how much of the temp VFX do you do?

Again, on low budget films, I do whatever I need to. But when I have the choice, I prefer to let my assistant or VFX Editor tackle making temp comps

If I have a very specific idea of what I want out of the comp, or if it’s timing-related (such as doing a split screen with separate takes on each side), or if it’s just so easy a comp that it would take me longer to ask for it than it would to just do it, then I’ll do it myself.

But generally I think you want the person who is responsible for managing VFX for the movie to also do the temps. It helps them keep track of the VFX needs for the film, and by doing the temps and receiving feedback from me or the director on each shot, it helps them better relay our needs to our VFX vendors later on.

How do you handle collaborating with a director?

I think it’s any editor’s job to get on the same frequency with a director, and understand exactly what they want the film to be. Once I’ve done that, then I can proactively make changes or spot problems, and not bother the director with every little question.

I also see it as my job to be completely honest with a director about what I think works and doesn’t work, and make my office a place where they feel comfortable doing the same.

Editors often become a director’s confidant, even about issues unrelated to the film, which I think is a sign you’ve established the mutual trust you need to work together in this crazy pursuit.

How do you handle collaboration with other depts?

Having as much knowledge as you can acquire about how other departments function is a great way to establish trust with them when you start working together. This is an area where my years as an assistant help significantly.

I know what the sound department needs from me and I know how to express what I need from them. I know how VFX shots are made, and that helps me communicate my needs to our vendors, or to realise in advance when a VFX shot will be more complicated than it seems.

With music, I have nearly two decades of piano training, and that helps me communicate with my music editor and composer.

Being able to speak the lingo of each department, understanding their processes and limitations, and using that to provide clear direction is how I like to work with other departments.

If there’s something I don’t understand about how a department is working, I have no problem asking what may be a dumb question in order to figure it out.

Any tips or advice for editors taking on their first feature?

Be ready to just go with the flow.

A first feature is likely a low budget feature, so you may have to do more than you anticipated, or deal with people who are less experienced than you are.

Be confident in yourself and your work, act like this isn’t your first feature, have a good attitude, and roll with the punches.

People remember you just as much when you’re easy to work with as they do when you’re a pain in the ass, and having a rep for the latter doesn’t do you any favours.

If you’re working for a first-time director, make them feel comfortable with the Post process.

It’s a black box for a lot of people, so it can be helpful and reassuring to a first-time director if you explain things like why your Avid dailies aren’t closer to the grade they imagined, how your sound mixers can fix most production dialogue problems, or to assume the role of in-house VFX Supervisor and call out problems with shots that they may not have the eye yet to spot.

I also think it’s important to work on projects that you’ll be proud to show when getting your next job.

If the script isn’t right, or there’s something off about the situation, find a different gig.

I think as a freelancer you have to be a little merciless about putting your interests and your career first, and that can mean saying no to people who have hired you before, or to an offer that’s attractive but doesn’t help you get to where you want to be.