Master Filmmakers on Film Editing

I’ve written about Masterclass.com a few times on this blog* because I absolutely freaking love it.

Where else can you learn from some of the most interesting, inspiring and insightful people on the planet, all of whom are true masters of their craft, whilst sitting in the comfort of your own home?

What I haven’t written about yet is what the entire library of courses, which currently includes 14 different filmmakers from Spike Lee to Natalie Portman, Martin Scorsese to Ron Howard via David Lynch, Shonda Rhimes and Aaron Sorkin (to name only half of them) has to say about film editing.

That is, after all, what this blog is supposed to be about!

So this post is a compendium of what Masterclass.com’s instructors have to say, specifically, about the art and craft of film editing, and what we editors can learn from them in general.

There are, of course, a million other practical insights on creativity, storytelling, character, sound design, dramatic structure, collaboration, etc. etc. to be enjoyed through all of the classes on Masterclass.com.

This is why the All-Access Pass is so worthwhile, and as they keep adding more and more interesting courses to the library, it’s becoming even better value.

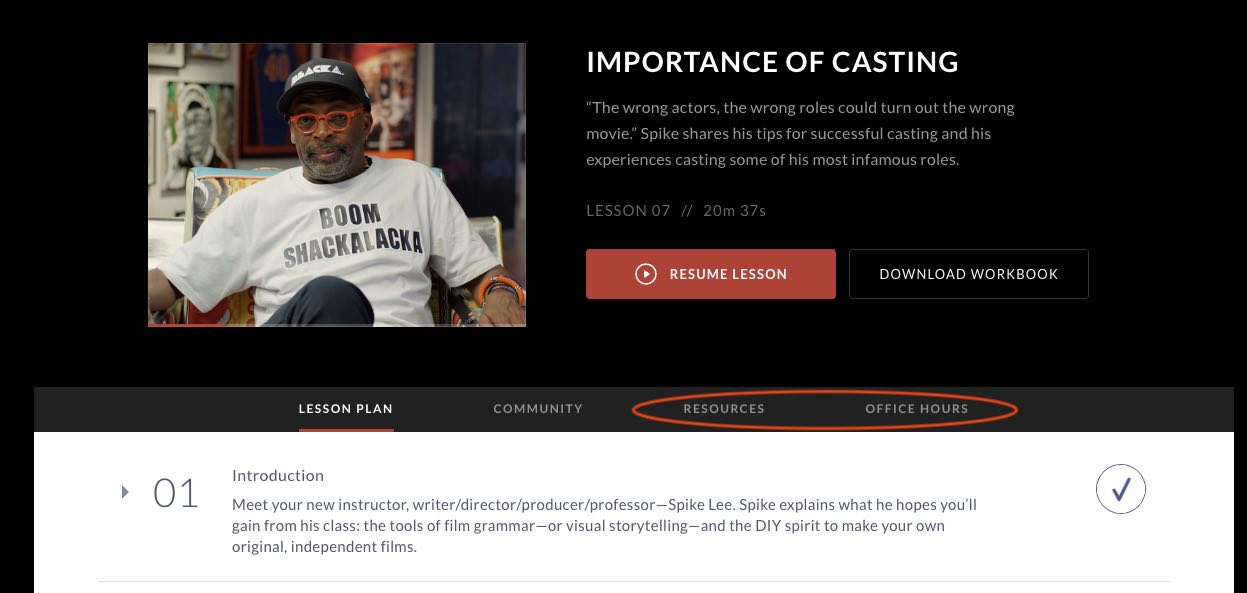

It’s also worth pointing out that each class also has downloadable resources to add to your learning, including per-lesson notes, script samples, reading lists and the like which you can find under the ‘Resources’ tab.. For some of the filmmakers there are also student Q&A sessions called ‘Office Hours’.

So if you read through my previous reviews of courses such as Hans Zimmer’s compelling and entertaining masterclass on film scoring or Aaron Sorkin’s exceptional masterclass on screenwriting you’ll soon see how much an editor can learn and apply to their craft.

*Here are the other times I’ve written about Masterclass.com:

- Masterclass.com All-Access Pass Reviewed

- Aaron Sorkin Screenwriting Masterclass Reviewed

- Hans Zimmer Composing Masterclass – An Editor’s Review

- Martin Scorsese Teaches Filmmaking Masterclass Review

- Masterclass courses for Film Editors

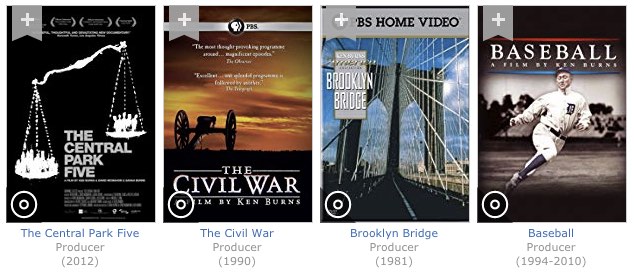

Ken Burns on Film Editing

Ken Burns is a master documentary filmmaker, who has been nominated twice for an Oscar, with some amazing insights to share in his masterclass.

What I loved about this course was how wise Ken Burns is – not just about filmmaking but about life. So often the things he says about filmmaking are to do with who you are as a person and how you operate in the world.

For example, he describes why it’s important to be humble with your own hold over the material, responding to what it needs rather than want you want it to be:

[Editing is] the merciless triage that everyone who wants to be a filmmaker has to come to face… You have to murder your darlings… and be willing to sacrifice them in the service of something else, that has gone places that you couldn’t even imagine.And it’s having a kind of courage to permit yourself to let it go in a direction that you didn’t think it was going to go.

The 26 lessons that make up the course deliver a huge amount of knowledge on process of dramatic documentary story construction but as I’m focusing on the film editing, there are actually 7 specific lessons that are particularly worth focusing on:

- 07 – Structuring a Documentary Narrative (14.34 mins)

- 18 – The Power of Music (15 mins)

- 19 – Editing: Process (10.34 min)

- 20 – Editing: Principles (10.24 min)

- 21 – Editing Case Study: The Vietnam War Introduction (18.42 min)

- 22 – Recording and Using Voice Over (9.30 min)

- 23 – Sound Design (11.20 min)

In the last month of editing there are sometimes some big and scary decision to make, additions, more importantly subtractions from it.

But most of it is opening up 2 frames, that’s a twelfth of a second. Opening up 6 frames, that a fourth of a second.

You can say that’s imperceptible but when you are as engaged in the editing process with us, it’s true. You feel it at that level.

In one part of the course Ken describes how when he was close to finishing his first film, his editor said that she was going to cut one single frame out of the entire film to see if he noticed where it was missing. And he found it.

His wish for every one who takes his course is that they would get to that level of engagement and connection with their own work that they can also say “Someone took a frame out of my film, and I want it back.“

As editors we need to balance attending to the details of each moment in just such a way, but also to be closely attuned to the rhythm and arc of the film as a whole.

Ken Burns Teaches Documentary Filmmaking on Masterclass.com

Ron Howard on Film Editing

I loved watching pretty much every minute of Ron Howard Teaches Directing, so much so that I wrote a much more in-depth review of it, which you can read here.

Ron’s love of filmmaking is palpable and incredibly inspiring. It’s also the best practical hands-on course that I’ve seen so far on Masterclass.com, and one that pretty much anyone involved in film production would benefit from watching, as it gives you such a strong overview of the entire process from the directors point of view.

In reality, the editing room is where the film is made, but you can’t think about it [during the pressures of production].

In Ron’s masterclass there are at least four chapters dedicated to the topic of post production, but there are also some amazing lessons to be learned for editors throughout the course, such as in the lessons on script evaluation or story structure.

- Editing: Part 1 (15.59 min)

- Editing: Part 2 (9.40 min)

- Sound Design (8.26 min)

- Music and Scoring (10 min)

[You should be] not just looking at one scene after the other, as it’s own discrete set of creative ideas and writing and acting problems, but trying to bundle things together and create a kind of a flow and an emotional connection that is building and crashing down – emotionally, and then you begin again, with a new narrative question.

What next?

Those kind of things, create emotional investment for audience, they also help you define ‘highlight scenes’.

Most directors would say your movie is built on a handful of highlight scenes… they’re usually a pay off to a sequence. Billy Wilder said you have to understand your five important scenes and know how to build to them.

During a course a movie there is not just one climax at the end, there’s meant to be a lot of spikes, and it’s the directors job to identify it and make sure you don’t under play those, and that also in the aftermath of one of those moments you give the audience a breath.

You understand that you’ve just completed one sequence with it’s own climax and give yourself a moment to collect yourself, and wonder what’s going to happen next and then move into it with the characters.

I think this is a great concept for editors to keep in mind, and also helps you to focus on building and blending transitions between scenes so that the sequence works as a whole. I remember reading an interview with an experienced editor telling his juniors not to worry about finding the perfect way to begin a scene, when cutting each one for the first time in isolation, because inevitably that beginning (and also ending) will be impacted by the scene that goes before and after it.

In many ways that’s why it’s important to get through the whole assembly before you begin fine cutting because the context outside of the scene will determine so much of the specifics that need to be drawn from it.

Read my detailed review of Ron’s Masterclass here or check out Ron Howard Teaches Directing for yourself on Masterclass.com.

Werner Herzog on Film Editing

Of all the filmmakers on Masterclass.com Werner Herzog is one of the most disarming in his approach to filmmaking and film editing as well. He’s a ruthless artist at heart.

I consider my footage as if I found it somewhere. Somebody else made it, so lets be curious. What’s there? What does the material tell you? What does it have to offer? And all of a sudden you discover elements in the footage that you would never have discovered if you had had a very strong will to enforce upon the footage. – Werner Herzog

A few specifics from his editing process include watching all of his footage only once, in about a one week run and making long-hand notes including timecodes and a ranking system of exclamation marks before beginning the edit. He memorises the footage and relies on his initial instincts on the footage.

He also makes ruthless choices throughout the process which includes throwing away unused footage at the end of the project – there’s no going back!

I hardly ever go back into the footage that I didn’t consider as being worth while to end up in the film. I do it sometimes. And sometimes it makes my editors nervous that I am so dismissive of things. I throw things away at once. And you have to be ruthless. Ruthless with your own material because otherwise you end up with a nine and a half-hour film.

After about half a year of a film being out in theatres, I would throw out all the outtakes, forever. They would be gone. And my argument is that a carpenter doesn’t sit on his shavings either. So you just plow through it. And you throw away and forever.

You have to take strong decisions… it can be quite painful but you have to learn it. How else can you stay away from endless tweaking, endless fiddling. You just have to have the nerve.

It’s a profession, it’s not raising a pet.

For modern editors the most difficult part of our digital workflow is that we can always go back. There’s always a back up, there’s always another way to explore, we can duplicate the sequence and cut a whole other film, very easily.

And this can make it hard to know or to trust ourselves that there is a singular way forward. That we can make definitive choices.

Throughout Werner’s course there are some more strong opinions on the process of filmmaking, including the process of market-testing a film “mostly a labyrinth of stupidity…”, his interview techniques and the artistic voice that comes from the film itself.

- Sound (10.08 min)

- Music (12.35 min)

- Editing (19.16 min)

- Documentary: Truth in nonfiction (15.22 min)

If you want to learn how to be a truly authentic filmmaker, taking Werner’s course will be a shot in the arm for you and a create counter-balance to the other more ‘American’ minded filmmakers. Spending a few hours with Werner will be well worth your time.

Werner Herzog Teaches Filmmaking on Masterclass.com

Spike Lee on Film Editing

I remember the first time I watched Spike Lee’s Clockers. There were so many filmmaking ideas, approaches and aesthetics in that film that immediately had a huge impact on my vision of what filmmaking could be.

Spike’s Masterclass is equally packed with ideas, opinions and stylistic approaches to filmmaking that can only come from the heart and mind of Spike Lee.

But for our purposes there are at least 5 lessons that we can focus on specifically as film editors:

- Opening Title Sequences (11.48 min)

- Music is Key (14.18 min)

- Editing (17.06)

- Film as an Agent of Change (8.31 min)

- Storytelling for Documentaries (6.49 min)

My biggest take away from Spike’s class was that if you’re a filmmaker it’s a privilege and you can and should use your art/platform/opportunity to say something.

At one point he discusses watching Birth of a Nation at film school and how the discussion led by the lecturer was all about the use of intercutting and the film’s revolutionary techniques, but what was entirely neglected was how the film led to the resurgence of the Klan. It was decontextualised.

So then, years later, in his own film BlacKkKlansman, Spike used the same technique of intercutting – between a Klan meeting and a black power meeting – to create a potent juxtaposition in order to make a political statement.

And so what’s great about the class is that it doesn’t shy away from the topic of race in film, and in the film business itself, and delivers some truly thought-provoking perspectives, not only from Spike’s body of work, but his personal experiences too.

Spike’s masterclass is also one of the only ones that includes a specific lesson on designing opening title sequences and how the combination of music, graphics and artistic visuals can set the tone for what the audience is about to experience. This lesson features some interesting observations from Spike on the opening titles of Mo’ Better Blues, 25th Hour and BlacKkKlansman.

Another takeaway, which reminded me of editor Walter Murch’s habit of taping a paper cut out of the backs of the audiences head, to the bottom of his client monitor, was Spike’s exhortation to ensure that friends and family screenings are projected in a theatre, and not viewed direct from the Avid on a small monitor. It’s just not the same experience and you won’t be able to evaluate the film in the right way.

The balance of the film really comes together for me in the editing room. That’s where you weigh the different parts you’re trying to do.

My films historically are not about one thing. They’re a mix-tape of many different things. For example, Do The Right Thing, is a very very serious film, with very serious subject matter. It’s not a comedy but there’s a lot of humour, in Do The Right Thing.

And so with my long time great editor, Barry Brown, we were able to find that balance because you don’t want to be lopsided one way or the other.

That first cut’s not going to be the balanced the cut you need. You just gotta keep working and working and working and working. – Spike Lee

The use of music is so predominant in Spike film’s that his course is a great place to learn more about working with music in your film editing and something that Spike said that stayed with me is that you shouldn’t “disrespect the music” by bringing the composer into the collaborative process as early as you can, otherwise “you’re saying the music can’t change anything, if they’re only working to a locked picture at the last minute.“

I really enjoyed Spike’s class and his infectious enthusiasm for the power of great cinematic storytelling is totally enthralling. Just watch Lesson 4 – Speaking Truth to Power: On The Waterfront and you’ll see what I mean.

Spike Lee Teaches Independent Filmmaking on Masterclass.com

Jodie Foster on Film Editing

I was curious to watch Jodie Foster’s masterclass on filmmaking because I’m not all that familiar with her work as a director, even though she has four feature credits to her name and has directed episodes on at least five major television shows too.

Jodie’s is one of the shorter film focused classes in the Masterclass library, with 18 lessons, some of which have a shorter running time, but there are plenty of gems to be enjoyed.

- Selecting a Performance Case Study: Jack O’Connell in Money Monster (5.19 min)

- Editing (18.54 min)

- Music (6.47 min)

Given that her directing credits span from the early 90’s through to today, Jodie has worked both with film prints and digital editing, and highlights just how formative the experience of physically editing on film was to her editing process:

In the old days (of working on film) you developed a skill of being able to really pay attention to what the performances were, to what the movements were. So that you could remember them, to bring them back, from take to take.

And say I like take 1 for this reason, I like take 4 for this reason. I like this line on take 3, I don’t like the wide shot.

To be able to make all of those choices you have to have a memory, a sort of emotional memory of what the actors are doing, and what the characters are doing, and also have a technical memory of what they’re doing physically.

(Even though it’s easier to toggle back and forth with digital editing) I still believe that your memory is your greatest tool.

She had some great insights to share on the editorial process, that stem from her decades of acting experience, which means that she finds it much more natural to associate herself with the characters, their motivations, their reactions and allow that to form how the scene should be structured.

So often I think as editors we stand one step removed from the characters internal motivations and experiences, because we’re judging – as a viewer – the best performance, or the best camera moves, the best visual compositions etc. But to pause to consider what each character’s motivation and goal is, within a scene and how those conflict with other characters, could help to shape our analysis of the ‘best’ takes to work with in the first place.

In the cutting room there’s a lot of adventures in figuring out when to hold them and when to fold them. (laughs) of what you hold onto, in terms of the vision of your film, int terms of the edit, and what you acquiesce to.

That’s a tough one. In the best possible world, you end the process feeling like you make exactly the film you were hoping to make, and that none of the cuts that you made were sacrifices. That they really made the film better.

And for the most part, most of my experience have been that way, but I have also had other experiences as well, and it can be very demoralising.

There’s nothing like how you doubt yourself and how painful a process it as being in the cutting room and knowing you see something that other people don’t see.

One of the huge benefits of the All-Access Pass is that you can afford to watch every and any class, because they’re all included, which really helps to add depth and diversity of opinion into your learning diet.

Jodie Foster Teaches Filmmaking on Masterclass.com

David Mamet on Film Editing

What is immediately apparent about listening to David Mamet teach dramatic writing, is that he can deliver a detailed, weighty monologue on a whole host of subjects, with interesting stories thrown in to boot.

So his lessons tend to be longer than some of the other instructors, but he’s fascinating to listen to, from start to finish.

Like Hemingway said “Write the best story you can, and throw out all the good lines.”

So that’s how you make a movie, anything that’s not the plot, throw it away.

David’s writing and directing credits are extensive, with features such as American Buffalo, The Edge, Wag the Dog, The Winslow Boy, State and Main, Hannibal and the legendary, Glengarry Glen Ross.

One of the core reasons for taking David’s masterclass is to get an intense education on dramatic rules, how to structure plot, case studies on American Buffalo and Glengarry Glen Ross and handling narrative, exposition and character dialogue. A ton of great stuff.

Here’s a taste of some of those lessons

- Dramatic Rules (11.48 min)

- Dramatic Rules (Cont’d) (8.22 min)

- Plot (16.14 min)

- Structuring the Plot (13.48 min)

- Structuring the Plot (Cont’d) (10.32 min)

- Case Study: Structuring the Plot – American Buffalo (21.30 min)

- Case Study: Structuring the Plot – Glengarry Glen Ross (21.45 min)

- Narration & Exposition (14.55 min)

He also directly references working with his long-time editor, Barbara Tulliver who has cut 12 or so of his features when he quotes her as saying:

There’s no rules, but there’s only one law and the law is don’t be boring.

Throw it away.

And throughout his lessons he frequently exhorts you to ‘throw it out’, when it comes to interesting but unnecessary scenes, plot points or even to ‘burn the first reel’ – to take the first 10 minutes and throw it away. You don’t need it as you can start your story in the middle.

For editors wanting to get a tighter grip on story structure, narrative arcs and how to tell great stories that an audience can follow and enjoy, David Mamet’s Masterclass will be well worth wrestling with.

David Mamet Teaches Dramatic Writing on Masterclass.com

Aaron Sorkin on Film Editing

Aaron Sorkin’s Masterclass on Screenwriting was my first experience of just how good Masterclass is. I reviewed it at length in this previous post. As huge fan of West Wing, The Social Network and Money Ball (plus I thought Molly’s Game was an impressive directorial debut!) I’ve always enjoyed his writing style and storytelling mastery.

We’re going to talk about Intention and Obstacle. Which is the most important thing in drama, without that you’re screwed blue.

Without strong clear intention and a formidable obstacle you don’t have drama. – Aaron Sorkin

If you read through my previous review you’ll find a whole host of reasons why editors should take his class, arising from the similar skillsets required to be a writer and an editor:

The edit is often called the final rewrite and for good reason, as editing is very much like writing.

An editor’s job is to know and utilise the principles of conflict, character, story structure and narrative arcs, as elegantly as any screenwriter. They tell the story with words, we tell it with rushes, but the results are the same. Pictures, sounds and structure woven together into one seamless story.

If you’re going to learn more about successful film and TV screenwriting then who better than Aaron Sorkin. (or Shonda Rhimes or David Mamet – hey they’re all on Masterclass!)

The other things that make Aaron’s class so enjoyable are to learn from his interaction with the writing students he works with in lessons 12-16 (their scripts) and 25-34 (West Wing writers room).

- Intention and Obstacle (10.11 min)

- Rules of Story (8.05 min)

- Film Story Arc (11.26 min)

- Scene Case Study: Steve Jobs (8.35 min)

- Scene Case Study: The West Wing (16.43 min)

Here’s one of the 5 things editors can learn from Aaron Sorkin’s class, from my previous post.

2. Find the conflict and focus on that

Generally the conflicts that I write about are ideas. It’s usually not robbing a casino that has the greatest security system in the world. It’s usually a conflict of ideas and what you want is for the competing ideas to be equally strong.

As an editor, if you don’t know what the central conflict is about you can’t craft the scene around it. If you just wade into the rushes (especially in documentary) without this to guide you then you will get lost and the audience will get bored.

Developing a clear understanding of the central and conflicting themes, characters and situations will help you to clarify and heighten the drama.

Aaron Sorkin Teaches Screenwriting on Masterclass.com

Hans Zimmer on Film Editing

Having watched a fair few different instructors on Masterclass.com, the thing that immediately sets some apart is the enthusiasm, engagement and entertainment value of the person. For a taste of what I mean, just check out the trailer for Timbaland’s Masterclass on music producing and beat-making and you’ll see that his joy is infectious! (The same could equally be said about Malcolm Gladwell or Commander Chris Hadfield for that matter!)

Another musician who displays all these qualities is composer Hans Zimmer.

If you’ve read my post on The Best Soundtracks to Work To, you’ll know that I’m massive fan of pretty much all his scores!

You’ll also see all of this in my extensive review of his Masterclass on Film Scoring.

The drummer for the film composer is the editor. so you need to know your editor and know how your editor feels tempo. – Hans Zimmer

One of the reasons film editors should watch Han’s Masterclass is not only will you learn a lot about how and what music brings to filmmaking – it’s structure, themes, character arcs and pacing to name a few things – but also how to work with a composer, understanding the language they speak and the goals they’re trying to achieve, so that you can collaborate in a far more harmonious fashion.

Some of the most helpful lesson for film editors in Hans Masterclass include:

- Directors: Part 1 (9.35 min)

- Directors: Part 2 (8.24 min)

- Directors: Part 3 (6.47 min)

- Sound Palettes (17.32 min)

- Scoring to Picture (12.13 min)

- Scoring Under Dialogue (9.13 min)

- Tempo (9.42 min)

There is a huge amount to learn from Hans, especially for editors who are in-effect working as their own composers when choosing music for themselves in their projects, about how to think like a composer.

I’ve included his lessons on working with a director because they’re invaluable for editors too:

This is the only bit of Masterclass that’s gong to be important.

When you start on a project, you are working with the director. Everybody else is secondary noise.

You and the director make a pact that you ‘re going to do this movie together, and you’re going to do your utmost and your best to go and make his film great. Even if it means you have to kill him sometimes.

But your allegiance is with the director.

And yes, what the producers say, and what the studio says – and they’re great comments, they’re amazing comments usually – and you have to take them on board, but you have to filter them and transform them into:

Is this helpful to the film the director is trying to make?

Because, I don’t know how else to do it.

Films aren’t made by committee. It seems like it sometimes, but not really.

Hans is an exceptionally articulate composer, who has worked with directors like Ridley Scott, Ron Howard, Terrance Malick, Christopher Nolan and many other greats, which makes him an entertaining storyteller with an amazing array of anecdotes and experiences to draw from.

I’m confident you’ll thoroughly enjoy your time with Hans, so don’t miss out!