You have to see Secret Mall Apartment.

It will restore your faith in art, humanity, and the power of documentary cinema.

One of the buzziest films at SXSW 2024, where it sold out 6 screenings – more than any other film at the festival that year and has racked up numerous audience awards on the festival circuit.

It’s a brilliant film that draws you in with its intriguing concept:

What happens when you set out to build a secret apartment inside an unused part of a busy shopping mall? And succeed?!

From there it does an artful job of drawing you deeper and deeper into a world that you never knew existed.

It’s a great film and I absolutely loved it. So I had to find out how it was made!

How to edit a documentary on opposite sides of the planet

The director and co-editor lives in New York, and the other editor in Melbourne, Australia.

So how do you cut a documentary together while apart?

In this article, you can take a deep dive into the making of the film with my conversation with the film’s director, Jeremy Workman, an award-winning documentary filmmaker and co-editor alongside Paul Murphy, who is both an exceptional editor and a superb Adobe Premiere Pro guru.

Among many other things, we covered:

- Co-editing from other sides of the planet

- How Topaz Labs saved the entire project

- A technique for decentralized editing no one seems to talk about

- Paul’s slow but fast approach to tackling hours of documentary material

- A unique Test Screening methodology that more filmmakers should try

But if you’re in the US, you should really see Secret Mall Apartment in the best way possible – in a cinema with other people – here’s a growing list of dates for an independent screening tour going nationwide.

These kick off with the Premiere at the Providence Place Mall on March 21st and continue through mid-April and beyond.

Where to watch Secret Mall Apartment

Here’s a short list of a few of the many places you can watch the film:

- Providence, RI – Providence Place Cinemas 16 – Opens Mar 21

- New York, NY – IFC Center – Opens Mar 26

- Austin, TX – AFS Cinema – Apr 4-5

- Los Angeles, CA – Alamo Drafthouse Downtown LA – Opens Apr 4

- San Francisco, CA – Alamo Drafthouse New Mission – Opens Apr 4

- Austin, TX – Alamo Drafthouse South Lamar – Apr 4 only

- Santa Fe, NM – CCA Santa Fe – Opens Apr 11

Inside The Secret Mall Apartment

Jonny Elwyn: Well, thanks for making time to chat. I’m super curious to ask lots of questions about it and I genuinely, absolutely loved it. One of the notes I wrote down was documentary is actually really hard.

Jeremy Workman: Thanks.

Paul Murphy: That’s why we do it.

JW: Yeah. Harder than scripted. Paul, would you agree with that?

PM: I reckon. I used to try and sit on the fence with that and go, yeah, but scripted has its own problems. But no, I think scripted has the advantage that the script has been worked on for five to seven years before you sit down to the edit. You’re doing that while you’re editing in documentary.

JW: You’re also beholden to performance with scripted and narrative stuff which removes the editor quite a bit compared to documentaries.

A collaboration origin story

JE: My first question is, what is the origin story of the two of you working together whilst working on other sides of the planet?

PM: I’ll be interested to hear what you say.

JW: I had known Paul for a fair amount of time just in the New York film geek, film nerd community. We have a lot of mutual friends. I was making films during that time while I knew Paul, and Paul was editing and working on his own stuff as well.

I really wanted to work with Paul, and I think it was when I saw the wine movie, Blind Ambition, which…

PM: Blind Ambition. It was at Tribeca.

JW: I had seen Paul’s work – short form stuff, long form stuff, funny and playful stuff. I knew he was also a prominent person in the Adobe world. But when I saw Blind Ambition, which was about this wine team from Zimbabwe that competes on the international level – it’s like an underdog sports movie, but it’s a documentary. It ended up doing really well and won a huge award at Tribeca.

PM: The Cool Runnings of wine films.

JW: What most impressed me was the range of style that Paul was bringing. One scene after another had a different style, which is really hard in documentary. You meet editors who are good at vérité or working with music or interviews and transcripts. But what was incredible with Blind Ambition was the different range of styles – playful, fun, serious, and heartfelt.

It was right around the time when I was thinking about Secret Mall Apartment, and I wanted it to have a similar feel – lots of moves, different styles, like a heist movie that’s fun and entertaining but also with profound, slower scenes. I thought Paul would be perfect for this.

Co-editing together, apart

JE: Okay, cool. But Paul, were you in New York at this time when you guys met?

PM: I reckon we probably met maybe, 2016, 2017. I had been living in New York since 2014 and we had to come back to Australia during COVID. That was like six years of being on the same film trivia team once a month. We were part of the same film culture in New York, so we would see each other a lot and have late nights where we just named directors all night.

It’s good because we did cut this remotely – I wasn’t in New York, he wasn’t in Australia, but we had an understanding of each other very well in our sensibilities before we cut a frame.

JW: Another thing worth noting is that I had done a handful of features and had never worked with another editor. That was a pivotal experience for me. It was important to find somebody that would be right for me to ease that, but also somebody that I wanted to bring their skill set and experience to the project.

The remote editing process

JE: I’d love to hear about the technical side, but I also love to hear about how that works day to day with the time zone? How did you split up the doing of it? What was the story of making the movie?

JW: The movie has incredible scenes that are almost like heist scenes using amazing old footage, this archival footage. Paul described them as sugar rush scenes. They filmed 25 hours when they were in the apartment using really crappy consumer cameras that were 320 by 240, 10 frames a second.

In the middle of that, there were other scenes where the movie was constantly shifting between different kinds of scenes – everything from recreation to scenes where a guy’s making a model of the mall to emotionally charged scenes where they were doing charitable art.

I was excited about this idea that the movie would switch gears a lot. Many of my documentary filmmaking peers are nervous about that – they don’t like when you feel the gear shift in a movie. But I love when movies switch on you and you’re going in one zone and then it switches gears. So it was easy to be like, “Paul, you’re on this stuff and I’m on this stuff.”

PM: I was incredibly nervous about that too. I was like, “But I don’t know what you’re doing.” But the way you split it made it cohesive. The fact that I was focusing on a self-contained story, and you were focusing on the other parts exterior to that made it work.

JW: The fact that Paul was in Australia on a totally different time zone – we deliberately avoided watching each other’s stuff in some ways. Certainly there were moments where I’d get a link at my 7 a.m. or I’d send him a link at my 3 a.m. We were keeping an eye on what we were doing, but the movie’s story allowed us this division of labor that enhanced the movie and let us each do our thing.

JE: So in terms of splitting it, who was doing which parts of the film?

JW: Paul had all the fun stuff.

PM: I had the fun, sugar rush stuff.

JW: Paul had all the scenes that evoked classic genre films – the crew sneaking in, all the stuff with the cinder blocks, and the interactions they had from 2003 to 2007.

I was handling the stuff that was more contemporary – people looking back or talking heads thinking about it as an idea from 20 years ago. But Paul had these scenes where he was like, “Okay, here’s your scene – eight people coming together, putting together this apartment, go.” And he would just go bonkers.

PM: It’s a dream because I had the footage where it was just like, these people have a plan, they’re trying to achieve something – can they do it or can’t they? That was very fun to work on every day.

Paul’s editing process

JE: How did you build those scenes and break down the archive?

PM: I was in New York at the very start. I had another job in New York at the time. Jeremy spent a couple of days in his edit suite where he showed me what he was looking for, and we got to geek out about the footage and talk about ideas.

Then I went back home with a drive. I watched the 24 hours of footage for a month. It was 24 hours that wasn’t shot for a film – it was just “Here’s a weird thing we’re doing. Let’s film it.” So it wasn’t shot with intention. Sometimes it wasn’t even shot with intention – the camera was accidentally on.

I built up probably 15 or 20 select sequences based on common themes emerging from the footage. Like where they’re building a wall – that would have its own select sequence. When they’re dealing with security – that had a select sequence. That was just a month of building up those sequences.

When it came time to start cutting the scenes, it was a fast process. I was going back to those select sequences and cutting them down. It allowed me to quickly find material. I think Jeremy and I are different editors – I like to spend a long time familiarizing myself, and then it’s a fast process. I can move really nimbly because I’m like, “That shot over there – I can put that in there.” But the start of the process is really slow, cataloging footage, cataloging it in my head so that when I’m ready to edit, I can improvise in the moment.

Technical Workflow

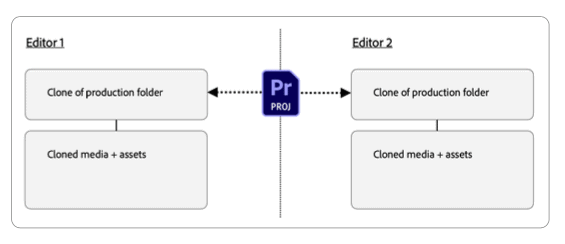

Decentralized collaboration using project files to share sequences.

JE: What was your actual technical workflow? I guess you cut in Premiere?

PM: We cut on Premiere, using Productions. It was probably Jeremy’s first time working with Productions. I had worked with Productions over Lucid Link in the past where you’re all working on a virtual drive, but in this case, we didn’t have that.

We did something I had stolen from Jarle Leirpoll who wrote documentation for Adobe Premiere Pro. It’s called decentralized editing. [See page 74].

Jeremy was the place where the film was being edited – his computer had the high-res footage, the proxies, and the production. But he could spit out a single project file that had just sequences in it, and the sequences had all of the footage I would work with.

That little project file could then be re-imported into his project without any duplicates. Rather than us working in a Production together, I was working in a satellite project file that could be taken back into his Production.

JE: What was it like working in Productions? Does it feel seamless, or does it feel like “I want to open this thing, but I can’t because the other person’s got it”?

JW: With the time zone difference, it felt like we were cutting 24/7. Paul would be on one schedule, I’d be on another. I’ve worked with editors on Productions where you can’t mess with what they’re working on, but that wasn’t the case here because Paul was in an all-proxy world and on such a different time zone.

PM: The film was never not being cut. But also, I was working in a project file not part of the production, which is difficult to describe. It could be imported into the production and become part of it, but there was no “he’s got it open so I can’t open it” issue. It was very separate – it had no footage in the project panel, only sequences with clips that would reference Jeremy’s production.

Nobody talks about this approach, but I think it’s how more independent films should work. It means there’s a single source of truth that an editor has, but you can create project files that others can work on and re-import without duplicates.

How to structure a documentary

JE: Did you have the whole film planned and mapped out when you started the edit? Often documentaries, you’re finding it as you go.

JW: When we started editing, we were fully shot. I’ve worked on projects where the edit happens alongside the shooting, and that’s hard. This one was where we felt like we had most of the material, even down to shooting recreations – those were scripted scenes.

It allowed us to be freer – I could focus on making an awesome scene about how they do tape art in hospitals, making it as good as possible. Then I trusted the process with Paul that we would go through and note card it and build it so that it has an arc.

PM: I don’t think you ever had to send me new footage. I don’t think I was ever waiting for footage. From that initial meeting in New York, that drive I took home with me – I never got any additional footage after that.

JW: Which is really rare. I don’t think that’s ever been the case on anything I’ve worked on or my previous films.

Technical challenges of low-fi footage

JE: Just a quick technical question about the super low-fi footage. Did you guys then up-res that or what was the process for making that usable?

JW: We did. We knew we would need to do something with it. It’s literally 320 by 240 and 10 frames a second. It was a big worry – is this an issue that’s going to mean we can’t play this theatrically, that a buyer wouldn’t want it because it’s so low res?

I started to ask around. I even spoke to a friend at the Criterion Collection whose job is to up-res old stuff for their Blu-rays. But it still wasn’t great. Then somebody suggested Topaz, which is an over-the-counter program, and it was shockingly good. It was better than the hardware solutions they use at Criterion.

PM: The film was delivered in 4K, so it’s 320 to 4K pictures. When we started getting concerned about it, I put it onto a TV screen and was like, “Yeah, that’s going to be a problem.”

JW: It was a real worry. One of these things where jumping into it, I thought we might not be able to exhibit it because of this issue.

JE: So when in the post-production process did you up-res it? Had you already started editing with the original footage?

PM: I cut with the original footage.

JW: Paul was cutting with the original footage. I was meanwhile doing experimentation on up-resing, settled on Topaz, and the rendering time is insane with Topaz.

I kept it going in the background on a system 24/7 for months.

A different kind of test screening

JE: What was the arc of your editorial process?

PM: Jeremy has a very specific process for screenings.

For me, screenings in the past were events where you hire a room and try to get as many people who agree with your opinion into that room. But Jeremy was very specific – he would go to people’s houses with the film, three or four people at a time. Sometimes he had to send them a link, but he’d prefer to be in the room with them.

He would watch it, pay attention to their reaction, and then discuss it afterwards. This is where you (Jonny) came into the story because I had received one of your newsletters about taking interview notes and using AI to distill that into actionable steps. So I tried that with the notes.

Jeremy was going to people’s houses with the film, three or four people at a time, and they were good people to discuss it with—they had strong opinions, and sometimes it rubbed him the wrong way, but it was good to get that kind of opposition early on.

JW: I believe movies are for audiences. The kinds of films I’m interested in making, and certainly this one – we want this to be audience-friendly in the most positive way. We want this to feel like a great experience.

The process was finding really good people – I have a roster of great people where I’m sitting on the couch with them, listening to feedback and reacting to it. Sometimes it’s helpful and sometimes it’s not, but creating that sense of what is working in an audience and what’s not.

This film has a lot of complex ideas, even though it’s fun and entertaining. It was important that we make sure that stuff was working. A lot of notable documentary filmmakers were watching it, and some notable scripted filmmakers too.

PM: People who knew to stick their fingers into the wound of something that wasn’t quite working. I’m guessing it was maybe 20 people in the end. You could have got those 20 people in a room and played it to them all at once, but I’ve come around to Jeremy’s approach – it’s more intimate, you’re closer to their reactions.

JW: There’s value in watching somebody’s reaction – how tied in are they to the story? Paul and I constantly talked about building laugh moments and building the footage so that it would have laughs.

PM: We were still talking about it at South by Southwest, celebrating when moments got laughs.

From temp score to final mix

JE: How did you approach the music in the film?

JW: Paul and I worked with a lot of temp music. I didn’t want to feel like we were just waiting on music – I wanted us to feel like we could cut the most amazing scene right now and not worry about the music. So we used library music, original stuff, score, anything we liked.

Then we settled on composers Olivier and Claire Manchon, who’ve done great work. It’s contemporary film score, maybe in the Jan Tiersen zone, using different instrumentation. But some of that stuff wasn’t totally right for Paul’s stuff because those scenes were more like what he was listening to – Lalo Schifrin.

JE: Did you do another polish pass and change things once you had the score?

JW: We did. There was some stuff where we tried things and it didn’t work – classic situations where it’s too heisty or feels like a Tarantino thing. We’d pull back and let the images build it.

PM: I just love the score for this so much. We saw the film five or six times at South by Southwest, and by the sixth screening, I really appreciated the total depth of the score – there are little themes very early in the film that come back later, not in a “here’s that same thing again” way, but like a little twist. The music is almost commenting on the themes as much as the subjects themselves.

JW: We were doing a lot with themes throughout the score, laying it in and figuring out how it would work. But like the movie, it was an opportunity for the composers to do different styles and sounds.

A clever way to use text captions

JE: One of the things I noticed was how the text captions reference how far you are from the mall at the beginning. Was that something planned from the beginning?

JW: We wanted to make sure a viewer would understand that this was a very small area and that everything was happening within this area. Michael Townsend’s home was half a mile away from the mall, and he did artwork a mile away. It was important to convey how everything is like a solar system with the mall right in the middle.

When I made “Lily Topples the World,” the lower thirds had people’s subscriber counts because it was about a YouTuber. Sometimes people would come on screen with 88 subscribers, sometimes with 30 million. I liked how the lower thirds were subtly giving more information. I think that was an idea we were in on pretty early.

Building on festival success

JE: What is it like to take your film to South By Southwest and have six audience screenings?

JW: It was awesome. I had been to SXSW before – my movie “Lily” won the grand jury prize there. But this was even more insane. Jesse Eisenberg is an EP on this movie, so he was also with us representing the film. The subjects came too. There was so much buzz about Secret Mall Apartment. Most film festival premieres are high stress, but it was a good time.

PM: I flew in from Australia two days early to acclimatize, but I was working on another project that I brought with me. I spent those days jet-lagged in a small Airbnb, working around the clock. The first time I saw anybody was when I saw Jeremy and the subjects (who I’d been cutting on my computer for months) in person, just an hour before the screening.

It was overwhelming. You can never anticipate how good it’s going to be to watch a film you’d been working on for months with an audience, and then answer their questions afterward. We had two screenings that night about 15 minutes apart. After the first screening, we went into the lobby talking to people, and then somebody told us we needed to go into the next screening and talk to everybody there. My heart just exploded at that point.

JW: We’ve had crazy audience responses at other festivals too. We had a screening with 3,000 people, and at the Melbourne Film Festival with about 800 people. It’s super fun to have a movie that audiences are really responding to.

Jesse Eisenberg as Executive Producer

JE: With Jesse Eisenberg’s EPing on it, what was the story behind that and how was that?

JW: He’s a friend of mine. He had previously EP’d another documentary of mine called “The World Before Your Feet” about a guy walking every street of New York City. Jesse loved it and the process. It was the first movie he had ever put his name on, and he ended up doing 25-30 Q&As with me.

He saw an early version of Secret Mall Apartment and said, “I want in, I want to be a part of this.” To this day, he’s still very active in it. There was an article in Variety last month about EPs who get involved in documentaries, and it featured Jesse in Secret Mall Apartment. He’s just part of the team.

Directing the release strategy

JE: What is the release plan strategy that you’re allowed to say so far?

JW: We felt like we were getting such great response in theaters that we didn’t want to just go digital or dump this on a streaming service. I had that experience with “Lily Topples The World” where we made a huge sale out of a festival and it just landed on a streaming service, and I was wondering if anyone was watching it.

I thought this movie should be seen with audiences in theaters. We decided to bypass traditional distributors for the time being (they’re still in our universe and watching what’s happening). With our own team and investors, we’re releasing this nationally in the US – we’ll probably be in 50 to 100 cities. We’re already booked in Boston, New York, LA, San Francisco, and Alamo Drafthouses.

In what’s probably the most incredible irony, we’re premiering at the Providence Place Mall on March 21st. I was at the mall yesterday and they love this movie and are excited to collaborate.

PM: Did I read right that they’re going to allow Michael back into the mall for the screening?

JW: We’re still discussing. But they’ve already put tickets up for sale at the mall, and there have been three news stories on the nightly news. The first screening already sold out a month in advance. The theater manager said Secret Mall Apartment is having a better response than films playing across all 20 theaters in their chain, even compared to Captain America.

(Avoiding) creepy editor vibe…

JE: When was the first time that Michael saw it? Was it at South By or had they seen early cuts?

JW: They had seen earlier cuts. As an editor and documentary editor, I always try to bring the subjects into the process earlier than other filmmakers I know. In this case, they were also contributing to the making of it – both in terms of the recreation and the building of that model. They were seeing versions, not necessarily giving notes, but they were in on it so they didn’t see it for the first time with an audience.

PM: That was a new process for me that I really appreciated. Traditionally in documentary it’s sort of like, “We’re the truth tellers, you stay over there and tell me your story.” This felt like there was more cross-pollination that really helped, especially from Michael.

JW: A lot of editors and filmmakers are nervous about that. I’ve always believed we have to break that barrier down and get comfortable with the process.

JE: Paul, when you saw them as you were jet-lagged, did you just hug everyone as if you were old friends?

PM: I have a word for it – it’s “creepy editor vibe” where you just know every tick of the person. I think I had that with Colin. I think Colin was maybe a little overwhelmed with how familiar I was with him. You’ve looked at this person every day, and now you’re seeing them in person. It’s always a weird moment to see somebody step off your NLE into the real world.